Dialectical Thinking: How To Develop World-Changing Ideas, According To Research

One of the most fundamental things a thought leaders does is come up with rare and valuable ideas:

Said differently, thought leaders need to think differently and better than others in order to succeed.

The question is, how do you do this?

Conventional wisdom is that you should learn a lot of rare and valuable things and then combine them in unique ways.

But, there is also another deeper way that is almost never talked about. In this article, I share fascinating research on how many of history’s most creative thinkers (Newton, Einstein, Darwin, Copernicus, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, etc.) develop ideas that change the world.

I’ll start by sharing my own personal journey to find and use this research…

Stage #1: Polarized Thinking

When I first became a voracious learner as a teenager, each new thing I found felt like the ultimate answer that would change everything.

Before then, all of the my thoughts had been the conventional thoughts of my mom, peer group, and school. I didn’t have or search for other outside knowledge.

So, learning about my entrepreneurial heroes who had philosophies that were different than anything I had ever been told was shocking. I wondered, how is it possible that no one ever told me about this stuff?

For example, I remember reading Think And Grow Rich when I was 16 years old, and going all in on goal-setting. Reading about how great entrepreneurs in history used goal setting was like a revelation at the time. Everyday, I wrote down a goal statement, printed it, framed it, and recited it. I thought that repeating it daily with passion would turn me into a millionaire within a year. I also told lots of my friends about it as if it were the ultimate discovery.

However, I didn’t become a millionaire after a year. Or even after two or three. After doing it daily for a long time, it felt like something was missing.

So, I found new things that I thought would change everything and fill in the hole…

Entrepreneurship

Writing

Hard work

Making an impact

Professional relationship building

Deliberate practice

And so on…

The never-ending search for the new, new thing happened in my personal life too. At one point, I thought things like supreme health, daily meditation, getting married, buying a house, or having kids would change everything.

Yes, each new thing made a big difference. But ultimately, each new thing didn’t match up to my unrealistic expectations.

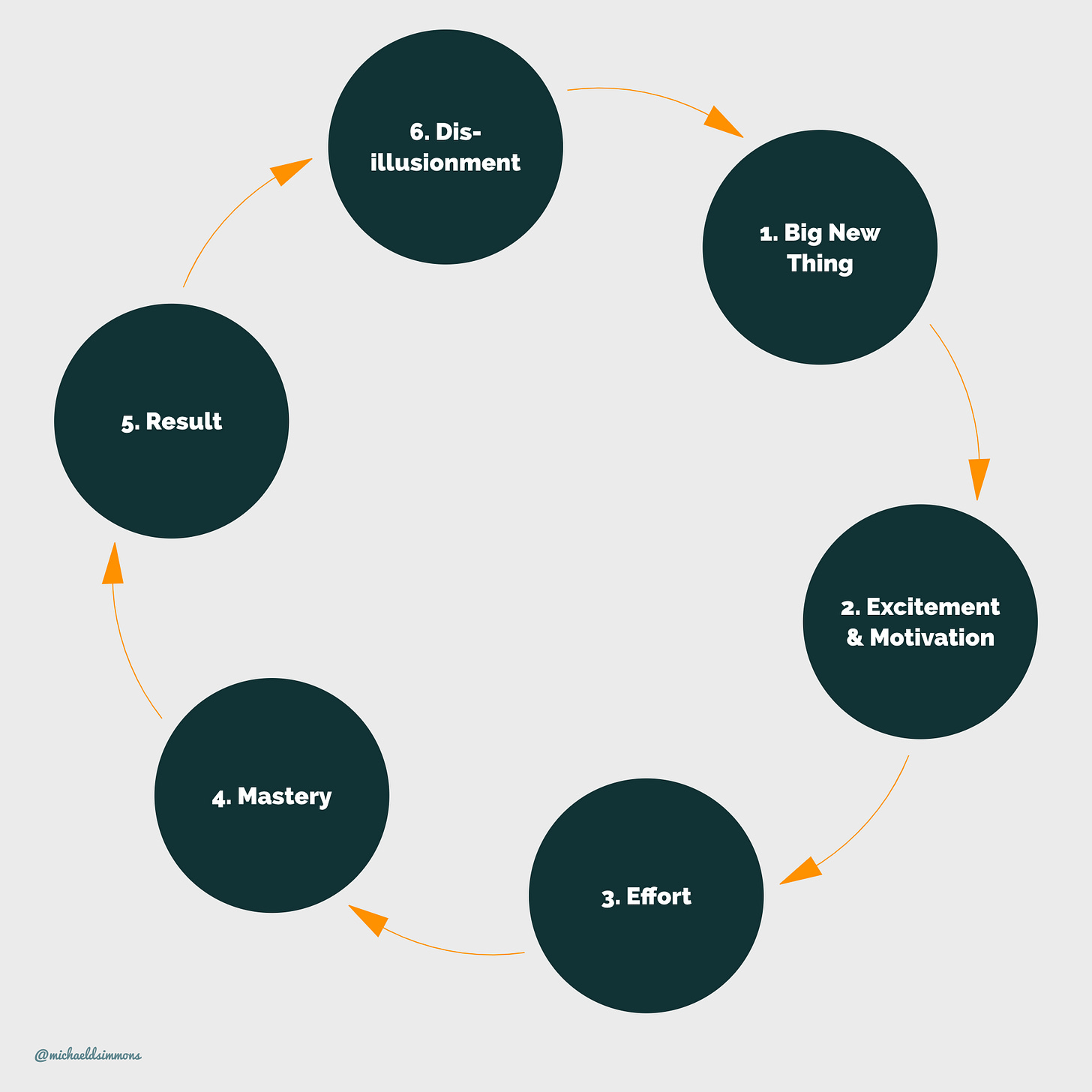

Eventually, I realized I was repeating the same loop over and over…

Finally, at around 30 years old, it registered with me that there would never be one ultimate thing that changed everything.

So for pretty much all of 2013 and 2014, I was disillusioned.

Being on a journey for the new thing gave me a lot of hope, purpose, and motivation to do hard things. Without it, I felt directionless, and I found it hard to muster the motivation I once had.

Summary: Looking back, I call this stage of my thought leadership journey Polarized Thinking. My thinking was polarized because I would:

Focus on one thing

Focus on all of its benefits

Ascribe unrealistic expectations to it

Ignore its limits

Minimize its disadvantages

I am grateful for this stage, because it empowered me to learn a lot of things that improved my life that I could share with others.

But, over time, I also saw its disadvantages…

My unrealistic expectations often resulted in poor planning and bad investments.

The highs of new possibilities were matched by lows of disillusionment.

Becoming laser focused made it hard for me to see the bigger picture.

While I was rushing for the new thing, I wasn’t fully appreciating, savoring, or experiencing life in real-time.

Starting around 2015, I entered a new paradigm that has transformed my life and career…

Stage #2: Dialectical Thinking

We can't solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.

—Albert Einstein

This stage was brought on by reading many academic papers and books in the area of developmental psychology, business success and creativity. As I performed this research, I noticed something shocking.

Researchers who were completely independent of each other were coming to the same exact conclusion. Not only that, the conclusion was something I had never even heard of before.

More specifically, in Studies Show That People Who Have High “Integrative Complexity” Are More Likely To Be Successful, I share four ground-breaking studies on top performers by Ray Dalio (Principles), Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Flow), Jim Collins (Good to Great), Roger Martin (business researcher), and Robert Kegan (adult development).

Collectively, these independent studies concluded that one of the most important and overlooked qualities of greatness is “integrative complexity” —the ability to fully master opposing skills and mindsets. For example…

Humility and confidence

Creative and analytical ability

Visionary and detail-oriented

Short-term and long-term focused

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi summarizes the collective findings with the following excerpt from his book Creativity:

If I had to express in one word what makes their personalities different from others, it would be complexity. By this I mean that they show tendencies of thought and action that in most people are segregated. They contain contradictory extremes — instead of being an ‘individual,’ each of them is a ‘multitude’…

These qualities are present in all of us, but usually we are trained to develop only one pole of the dialectic. We might grow up cultivating the aggressive, competitive side. A creative individual is more likely to be both aggressive and cooperative, either at the same time or at different times, depending on the situation. Having a complex personality means being able to express the full range of traits that are potentially present in the human repertoire but usually atrophy because we think that one or the other pole is ‘good,’ whereas the other extreme is ‘bad’…

A complex personality does not imply neutrality, or the average. It is not some position at the midpoint between two poles. It does not imply, for instance, being wishy-washy, so that one is never very competitive or very cooperative. Rather it involves the ability to move from one extreme to the other as the occasion requires.

Although my mind was blown away by this fascinating research, I wasn’t sure how to apply it. That’s when I went a level deeper into the field of adult development. Researchers that particularly influenced me are Jean Piaget, Sara N Ross, Theo Dawson, Barry Johnson, Michael Commons (Harvard professor), Susanne Cook-Greuter (Harvard trained), and Robert Kegan (Harvard researcher).

Slowly, I cobbled together a methodology based on the research I was finding, and I noticed that my thinking started to transform. I was coming up with paradigmatic ideas rather than more simple ideas based on hacks and habits.

In this new stage, rather than just focusing on one new thing, I focused on how each thing I learned fit together like a tool on a Swiss Army knife. Said differently, each new thing was a variable within a larger equation.

For example, I started to ask myself more nuanced questions…

Which tools are best used in different contexts?

How do the tools work together in combination?

What is the relative value of each tool?

What are the limits of each tool?

Eventually, I came across a step-by-step process that I have now been using for years.

What follows is a breakdown on each step…