Tutorial: How To Become A 6-Figure Curator In One Year

One idea can change the world.

At their best, ideas are gifts we give to the universe. Invisible angels that whisper into people’s souls transforming how they think, act, and feel for the better. For better innovations. For more happiness. For more personal growth. For better health. For better systems, leaders, and institutions. For a better world.

Ideas are things. Things we give birth to. Stones we throw into the pond of humanity that ripple out from mind to mind, mixing and matching in ways we could never predict or know.

They are messages in a bottle that flow around the world instantly—turning strangers into friends. They are lighthouses that shine the way for kindred spirits.

For all of these reasons, I believe in the power of the people who create ideas—the idea parents—the thought leaders.

And that’s why I’m obsessed with helping experts go from zero to one as thought leaders.

Zero is struggling to gain attention online.

One is:

Earning a substantial side income or full-time living from thought leadership

Becoming a recognized expert in the field

Improving reader’s lives

Loving the process

Everything I’ve focused on as a teacher over the last four years has been in service of this endpoint. While many teachers focus on automating themselves out of their course once it’s good enough, I have focused on maximizing contact with students so I can see what creates life-changing results and improve the program accordingly.

This approach has given me a deeper understanding of the obstacles that thought leaders face.

The brutal reality is that going from zero to one is the hardest step and most people fail. For me to eventually break through, it took years of painful trial-and-error where I felt invisible followed by years of not doing anything because I had given up.

The good news is that going from zero to one is 100% doable for people who are consistent, patient, and deliberate about improvement. When I decided to focus on quality and commit to thousands of hours of deliberate practice in order to improve as a thought leader, everything changed for me. I sincerely believe if you have these qualities too, then the question of success is a matter of ‘when’ rather than ‘if.’

The goal of this post is four-fold:

Show you how feasible it is to be a 6-figure curator in today’s digital age

Help you understand the #1 challenge that’s likely to get in your way that’s probably not even on your radar

Help you solve that challenge

Provide you with a template that is the result of 100+ hours of research (paid subscribers)

Let’s do this…

What It Takes To Be A 6-Figure Curator

To make $100,000 a year, you need to make $8,333/month.

To make that, you need 833 subscribers paying you $10/month.

See below for other amounts that get you to the $8,333/month figure (the table shows the annualized revenues)...

To get to 833 subscribers in 365 days, you need an average of 2.3 new subscribers per day.

While 833 subscribers is a lot, it’s feasible.

With that context set, let’s go deeper into the fundamental problem that stops people. I always start with the core problem because…

A problem well-stated is a problem half-solved.

—Charles Kettering (former head of innovation at General Motors)

The Cold Start Problem Of Going From Zero To One As A Thought Leader

The #1 challenge for experts who want to rise above the noise of the Internet is the Cold Start Problem.

No moment is harder than the very beginning of the journey.

This is true on two levels…

Challenge #1:

You have few skills, time, and/or followers when you start

In my experience, most niche experts aren’t coming onto the online scene with a huge budget to build a team and pay for ads. They aren’t coming with dozens of hours a week to devote to thought leadership. They aren’t already masters of online communication.

Rather, they only have:

A few followers who will see their posts when they publish them

Limited thought leader skills, because they haven’t been deliberate about learning the necessary skills and mindset yet

Limited time to devote to it, because it doesn’t make money

Limited research stored in their note system which they can easily cite

Challenge #2:

The bar to rise above the noise online is extremely high

To stand out to the point where people you don’t know read and share your work, you need to do one of two things:

Rise above noise in algorithms (social media, Google, Gmail). Your content has to be more engaging (shares, likes, comments, time on post) than other content in order for algorithmic news feeds to feature it. The challenge with this is that social media is already filled with skilled full-time individuals who have big followings that love them.

Create content that’s so good that strangers will share it. In other words, you can’t just create content that is readable. You have to create content that is so gripping that someone will feel the need for other people in their life to know about it. It also needs to be sharable by publications and other blogs. In other words, it’s not enough to just do a guest post. You want your writing to be so good that publications will promote it to all of their social media followers and email subscribers because it’s in their interest to do so.

While the details of the Cold Start Problem differ from field to field, it is a universal and timeless pattern…

The Cold Start Problem Is Universal

The distance is nothing; it’s only the first step that is difficult.

— Marquise du Deffand

The pattern is so universal and important that well-known Silicon Valley investor Andrew Chen wrote a whole book on it as it relates to consumer apps…

Summary

To succeed as a thought leader, you need to fully take stock of the Cold Start Problem:

You have few skills, time, and/or followers when you start out

The bar to rise above the noise online is extremely high

Simply winging things by posting lots of content is a recipe for failure and disillusionment. Just as much as it’s delusional to walk onto a golf course for the first time, take a bunch of swings, and expect to be a threat to professionals.

Rather, you need to have a realistic strategy to overcome the Cold Start Problem.

Unfortunately, most people don’t…

Cold Start Paradox: At the exact point beginners should be humble, they’re overconfident

Given the difficulty of The Cold Start Problem, you would think that people beginning their thought leadership journey would be very cautious. But, the opposite is true. People beginning their thought leader journey are often overconfident because they don’t know what they don’t know. This is a big deal on multiple levels:

#1: It causes you to run into problems you could’ve avoided with preparation

To know how to deal with what you don't know is more important than anything you know because the world is so much more surprising than you can really be sure of.

—Ray Dalio (self-made billionaire investor)

Invert, always invert: Turn a situation or problem upside down. Look at it backward. What happens if all our plans go wrong? Where don’t we want to go, and how do you get there? Instead of looking for success, make a list of how to fail instead — through sloth, envy, resentment, self-pity, entitlement, all the mental habits of self-defeat. Avoid these qualities and you will succeed. Tell me where I’m going to die so I don’t go there.

— Charlie Munger (Warren Buffett’s longtime business partner)

#2: It makes you under-invest in learning

If you think you know everything, you will learn nothing. If you think you know nothing, you will learn everything.

—Michael Simmons

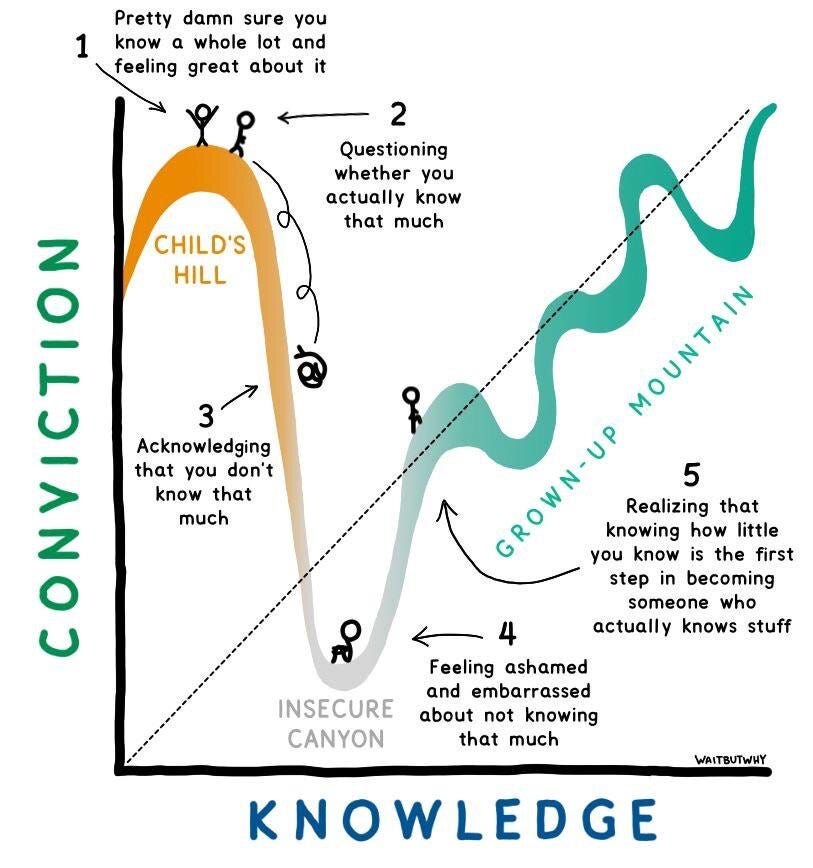

This Paradox Is So Universal That There’s A Name For It: The Dunning-Kruger Effect

In short, The Dunning–Kruger effect is:

A cognitive bias in which people with limited competence in a particular domain overestimate their abilities.

—Wikipedia

Tim Urban of WaitButWhy illustrates the phenomenon perfectly in this chart…

Here’s what people don’t know they don’t know when they’re getting started with a new field…

The quantity of skills required for mastery. Most people only see 1% of the skills necessary for success.

The relative importance of the skills. Not all skills are created equal. Some skills provide 10x the return of other skills.

The sequence that skills should be learned in. Just like we need to learn our numbers before we learn addition, certain skills depend on prerequisites. Learning skills out of order results in hitting a wall with progress.

The holistic transformations beyond skills that must be done in order to get the result. This includes shifts in mindset, paradigm, emotional regulation, values, developmental stage, and more.

The maze they must walk to reach their goal. This means making the right choices with the most important decision. Most people don’t know what the big decisions are, let alone the options, pros and cons of each option, and the implications over time.

The cause-effect relationships. Most people don’t understand the dynamics of what causes people to pay attention to, pay for, apply, or share knowledge. They don’t understand what the varieties of greatness in the field look like and how they were created.

As a result, aspiring thought leaders:

Drastically under-estimate how long the journey will take

Drastically under-estimate the difficulty of the journey

Wing it

Are overconfident

Are less likely to succeed

Bottom line: Most beginners come to the “thought leader” gunfight with knives and get killed. They underestimate the challenge of going from zero to one because of how they handle what they don’t know they don’t know.

The good news is that now that we understand the fundamental problem that stops early-stage thought leaders, we can mount a much better solution...

The Cold Start Solution

1. Be productively paranoid

2. Understand the big picture from those who understand it

3. Create a Foothold Strategy

4. Get your first 1,000 true fansStep #1: Be productively paranoid

We can learn about the power of productive paranoia from famous Stanford researcher turned bestselling author of Good To Great Jim Collins. In his less well-known but compelling book, Great By Choice, he shares a story that perfectly illustrates how to succeed and fail with the Cold Start Problem :

In October 1911, two teams of adventurers made their final preparations in their quest to be the first people in modern history to reach the South Pole. For one team, it would be a race to victory and a safe return home. For members of the second team, it would be a devastating defeat, reaching the Pole only to find the wind-whipped flags of their rivals planted 34 days earlier, followed by a race for their lives—a race that they lost in the end, as the advancing winter swallowed them up. All five members of the second Pole team perished, staggering from exhaustion, suffering the dead-black pain of frostbite and then freezing to death as some wrote their final journal entries and notes to loved ones back home.

It’s a near-perfect matched pair. Here we have two expedition leaders—Roald Amundsen, the winner, and Robert Falcon Scott, the loser—of similar ages (39 and 43) and with comparable experience… Amundsen and Scott started their respective journeys for the Pole within days of each other, both facing a round trip of more than 1,400 miles (roughly equal to the distance from New York City to Chicago and back) into an uncertain and unforgiving environment, where temperatures could easily reach 20 degrees below zero Fahrenheit even during the summer, made worse by gale-force winds. And keep in mind, this was 1911. They had no means of modern communication to call back to base camp—no radio, no cell phones, no satellite links—and a rescue would have been highly improbable at the South Pole if they screwed up.

One leader led his team to victory and safety. The other led his team to defeat and death.What separated these two men? Why did one achieve spectacular success in such an extreme set of conditions, while the other failed even to survive?

Collins answers this question a few paragraphs later:

Amundsen’s philosophy: You don’t wait until you’re in an unexpected storm to discover that you need more strength and endurance. You don’t wait until you’re shipwrecked to determine if you can eat raw dolphin. You don’t wait until you’re on the Antarctic journey to become a superb skier and dog handler. You prepare with intensity, all the time, so that when conditions turn against you, you can draw from a deep reservoir of strength. And equally, you prepare so that when conditions turn in your favor, you can strike hard.

Robert Falcon Scott presents quite a contrast to Amundsen. In the years leading up to the race for the South Pole, he could have trained like a maniac on cross-country skis and taken a thousand-mile bike ride. He did not. He could have gone to live with Eskimos. He did not. He could have practiced more with dogs, making himself comfortable with choosing dogs over ponies. Ponies, unlike dogs, sweat on their hides so they become encased in ice sheets when tethered, posthole and struggle in snow, and don’t generally eat meat. (Amundsen planned to kill some of the weaker dogs along the way to fuel the stronger dogs.) Scott chose ponies. Scott also bet on “motor sledges” that hadn’t been fully tested in the most extreme South Pole conditions. As it turned out, the motor-sledge engines cracked within the first few days, the ponies failed early, and his team slogged through most of the journey by “man-hauling,” harnessing themselves to sleds, trudging across the snow, and pulling the sleds behind them.

Takeaway

In other words, Amundsen prepared better than Scott for what he didn’t know he didn’t know. His productive paranoia made all of the difference.

Collins' story, albeit brutal, is a perfect metaphor for the Cold Start Problem broadly and the difficulty of achieving success as a thought leader more specifically.

It illustrates how to think about embarking on challenging, uncertain journeys. And because of its usefulness, I still remember it more than a decade after I first read it while flying in a plane to a speaking engagement.

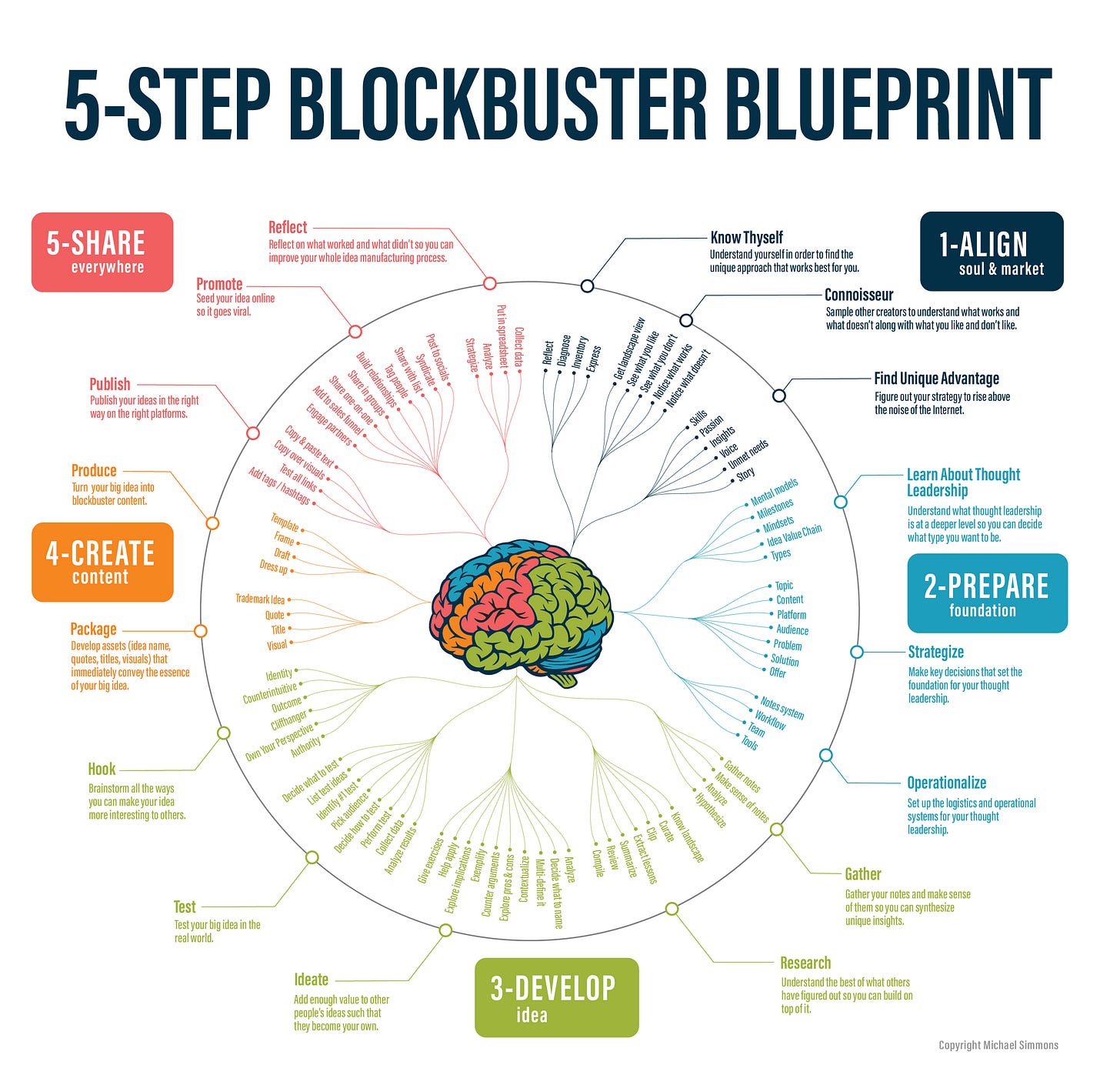

Step #2: Understand the big picture from those who understand it

The brutal reality is that if we’ve never done something before, there is no way for us to have a map on day one. And it would take us years of trial & error to build one on our own.

Understanding the maps of other thought leaders can drastically reduce your Don’t Know You Don’t Know blindspot.

Over the last 10 years of studying thought leadership, I’ve created the following blueprint…

In the coming weeks, I will break down all of the steps:

What the steps are

What sequence they should be in

What their relative importance is

When we put the right steps in the right order, we build momentum…

When we put the steps in the wrong order, we either fail to start or quickly lose momentum…

Step #3: Create a Foothold Strategy

The idea of a foothold comes from rock climbing. Before a rock climber can pull themself up by their arms, they need to first find a foothold they can put their weight on.

Similarly, when getting started as a thought leader, we need to find a foothold that is feasible, a step forward, and with immediate benefit. More specifically, we need to:

Create posts consistently

In a way we enjoy

At a level of quality that gains traction

In places that reward quality

Without a foothold to help you focus, the most likely outcomes are that:

You’ll get overwhelmed by how far away the summit is and never get started

You’ll get overwhelmed and just throw stuff up on the wall of social media, but not get traction

You might get lucky and get a hit but fall back down again because you lack the skills to capitalize on that luck

Most thought leaders don’t give up because of money. They don’t have many costs compared to a business. They give up because they give up. In other words, they lose hope or confidence in themselves or the feasibility or the desirability of the result. This is the “Death Line”.

With each step in the thought leader journey, you want to find a foothold and you want to avoid the death line.

Later in this post, I'm going to point out all of the footholds you'll need to find in your climb toward thought leadership, so you'll know where to put your feet for every step of the journey.

Step #4: Get your first 1,000 true fans

Rather than just looking at the solutions in the thought leadership field, we can look more broadly at how other fields have solved the problem.

For example, Lenny Rachitsky wrote an incredible post detailing how the top consumer software companies got their first customers…

Tim Grahl wrote a similar book for the book publishing industry…

In a future post, I will write more about getting your first 1,000 followers.

After Thousands Of Hours Of Research, This Is The Best Foothold Strategy For Thought Leaders Right Now

After years of helping students find their way from zero to one, I’ve found four footholds that I almost universally recommend…

Topic that makes you feel like a kid in the candy store

Focus on short-form video clips

Publish and monetize via a paid newsletter platform like Substack

Curate (rather than create)

Caveat: If you already have a following on a platform or proven skillset that’s related, your footholds may be different.#1. Select a topic that makes you feel like a kid in the candy store

Find a subject you care about and which you in your heart feel others should care about. It is this genuine caring, and not your games with language, which will be the most compelling and seductive element in your style.

—Kurt Vonnegut

If you don’t enjoy the process of researching, thinking about, writing about, and connecting with people on your chosen topic, then ultimately you likely won’t put in the energy and duration necessary to succeed.

Furthermore, if you aren’t excited, then readers won’t be able to feel your excitement. Therefore, your writing won’t be as compelling.

I write more about this topic in So Passionate You Never Stop Improving: The Secret Behind the Success Of Asimov, Jobs, Seinfeld, Oprah, Buffett, Newton, And All The Greats.

#2. Focus on short-form video clips

In How To Easily Curate Short Form Video Clips In Order To Rise Above The Noise Of The Internet, I explain why I think short-form video clips are such a big opportunity for getting started:

Editing video is way easier than you think

Social media algorithms love short-form videos

Short-form video is a limited-time opportunity

Short-form video is engaging to consume

Short-form videos can be combined into longer videos

Short-form video helps you research long-form content

Finding video clips is way easier than you think

Short-form is easier to produce than long-form

Over the last 9 months of sharing 150+ video clips on LinkedIn, I’ve seen my reach 6x. This increase in momentum is significantly more than anything I’ve experienced in the past in such a short time.

#3. Publish and monetize via a paid newsletter platform like Substack

In Why Paid Newsletters Are The #1 Way To Monetize Your Knowledge, I provide 10 core reasons why newsletters are a great channel to focus on in order to get a foothold compared to SEO (search engine optimization) or social media:

Email addresses hold their value more than social media followers over the years.

Paid newsletters allow you to focus on just creating great content rather than having to learn a basket of complex skills (growth hacking, funnel hacking, teaching, etc.) that take years.

Paid newsletters are 100x more viral than courses, coaching, and consulting because every newsletter post is sharable.

You get to spend most of your time on what you love—if you love learning and writing

You can scale without needing to build a big team or make big investments.

Having a public posting schedule is a super powerful forcing function that boosts your productivity by holding your feet to the fire.

Paid newsletters create feedback loops that lead to virality and money—not just virality.

It's super easy to get started on multiple levels—financially, mentally, etc.

Paid newsletters stay top of mind because they are pushed an email for every post.

Paid newsletters are easier to consume, because they appear in full in your inbox, without the need for logging into a course management system or clicking to another site.

#4. Curate (rather than create)

There are three ways to produce content:

Actively Consume (interact with other people’s content)

Curate (package other people’s content)

Create from scratch (based on other people’s ideas)

In my opinion, curation is the best approach for most experts to start with for a few reasons:

You can curate other people’s content that is already proven, which increases your odds of getting traction. Platforms are a giant experimentation engine where billions of people create content and the results of those experiments are public. We increase our odds of success when we build upon what has already been proven to work rather than creating from scratch—especially when we are just beginning.

It’s easier to do than creating your own idea. To create an idea, we typically combine and synthesize our own experiences and other people’s ideas. This is a higher-order action than curation.

What you learn from what you curate will be fodder for your own ideas in the future. For example, in So Passionate You Never Stop Improving: The Secret Behind the Success Of Asimov, Jobs, Seinfeld, Oprah, Buffett, Newton, And All The Greats, I share 13 videos that I originally curated and published as individual videos.

Even though you’re sharing other people’s ideas, you’re still building your reputation as a thought leader. When you distill videos and make them applicable, readers get a sense of your expertise.

It helps you get higher usage of your research. Rather than spending hours doing research and throwing away most of it, because it doesn’t fit into your article, you can immediately turn your research into an asset.

People are willing to pay for curation. The Internet is noisy, and algorithms are not designed for learning. Readers now understand what they’re missing, and they’re willing to pay for someone to sift through the noise. As you’ll see in the examples I share further down this post for paid subscribers, there are many success stories of people building huge followings and creating wealth from curation alone.

The curation opportunity is surprisingly untapped. Most niches don’t have even one person actively curating content around. This is something that I continue to be surprised by.

It will help you post more regularly. Posting and seeing people’s feedback provides motivation, enables you to understand which ideas to focus on, and helps you find improvement opportunities.

Get Started: Find Your Curation Niche (Paid Subscribers)

In So Passionate You Never Stop Improving: The Secret Behind the Success Of Asimov, Jobs, Seinfeld, Oprah, Buffett, Newton, And All The Greats, I write about the power of Infinite Devotion (foothold #1).

In this newsletter, I’ve previously written a fair amount about how to find, edit, and distill short-form video clips (foothold #2).

And I recently wrote about the power of newsletters (foothold #3).

But, I have not yet delved into how to curate (foothold #4).

The first step to video clip curation is understanding the universe of things you could curate video clips of. Over the last three years of understanding the power of curation, I’ve spent hundreds of hours just studying how other people curate content and experimenting.

In that time, I have:

Collected hundreds of examples of successful curation on social media, in books, in newsletters, and even in software

Identified what was most successful

Categorized what people curate

Experimented with curating video clips, quotes, visuals, and questions related to my niche.

Below is a 30,000-foot view of curation space that you can use to find unique opportunities that are under-served…