An Ambitious Person’s Brutally Honest Take On Work-Life Balance

Author’s Note: This article was written over 60 hours with love and care using the blockbuster mental model. It was originally published on Medium where it had 50,000+ likes.

We hit rock bottom. Now, we’re happily married for 12 years. Here’s what I learned.

Jim was both a serial entrepreneur and a serial husband.

In his early 60s, he was on his sixth wife and third company. He was about 70 pounds overweight.

I happened to sit next to him for dinner at an entrepreneurship conference. At age 28, I had just become a father, and I asked him a deep question that I was struggling with.

You have a 70-million-dollar company. Looking back, could you have been a better husband and parent and still built such a successful company?

His answer was both short and shocking: “Can a woman be half pregnant?”

I smiled politely and gave an uncomfortable laugh. In my head, I thought to myself, “Bullshit! I will prove you wrong!”

That was nine years ago. Today, my daughter is 9, and my son is 7. Looking back on that night, my conclusion can be summed up in three words:

Jim was right.

So this is how a marriage ends.

That’s what went through my mind, five years after that conversation with Jim, as I hung up the phone in my hotel room after a lifeless conversation with my wife and business partner Sheena.

The idea that two people who were “meant for each other” could just grow apart never seemed like a suitable cause of separation. But now I was living the possibility of it, and I understood.

At some level, I longed for the arguments of the past, which would at least confirm that we both still cared. But willpower no longer worked as a way to create emotion. For the first time in the 13 years that I’d been with Sheena, I was losing hope. I was scared.

This phone call happened immediately after a five-month sprint in which Sheena and I worked seven days a week to meet an impossible business deadline. Everything else in our life suffered: our health, our relationship, our parenting, our sleep. Each of us had aged three years in three months and we could see it in the other. In order to recover and get through the days with energy, I didn’t need one nap, I needed two. It was our low point as a couple and my low point as an individual. We were so busy we couldn’t even argue. Disappointment turned into anger, which turned into apathy.

When things fall apart, there are two ways to get back up:

Try to rebuild the life you had before.

Let go of who you were and become something new that you had never imagined before.

I chose the second path. So did my wife.

I remember us taking long walks in the woods, having multi-hour conversations, and journaling daily. I read books about how others confronted loss, so I could learn how to let go and live. These books included How We Die: Reflections of Life’s Final Chapter, in which a surgeon shared a behind-the-scenes perspective of patients’ final days. I also read Chasing Daylight: How My Forthcoming Death Transformed My Life by the former CEO of KPMG, Eugene O’Kelly. I was shocked to learn how, after decades of working long hours, O’Kelly quickly and with no regrets shuttered all ties with KPMG upon learning of his terminal diagnosis. I also read books about spouses losing spouses and parents losing children.

My loss, of course, could not compare to actual death, but on an unconscious level, I knew that part of me was dying. I felt real grief for the loss of goals I had been committed to for more than a decade, networks I had been a part of that no longer represented how I thought of myself, values that no longer served me, and beliefs about myself I no longer wanted. The period ended with both Sheena and I making serious changes to who we spent time with, how we managed our health, who we chose as role models, how we parented, and how we conducted our relationship.

For example, I took a deep dive into health. As a result, I learned that I had mild sleep apnea, a gluten allergy, and a vitamin D deficiency. I started tracking my physical movement, exercising regularly, and sleeping more. Sheena took a year off of work to be full-time with our son after he had to transfer out of two preschools and had become mute in any school environment.

I’m now proud Sheena and I have been together for 18 years and married for 12. We’re more financially secure than ever. Our son is thriving in a perfect program for him. And we love what we do on a day-to-day basis because it is deeply, intrinsically rewarding. Finally, we can both honestly say that the relationship is better than it’s ever been.

Jim was right because being great at something, to truly be one of the best in the world in a professional context, typically requires an ungodly amount of commitment over decades. It requires rising to and overcoming every challenge. This commitment often comes at a cost: to building friendships, to a deep relationship with your spouse, to your health, to your children, and to whatever else requires time and energy.

Ambition can become a vacuum that sucks in everything in its path. It’s what you think about in the shower, on your commute, or during any idle moment. I’ve read more than a hundred biographies of elite performers and have yet to find one who was not consumed with being world-class to the point of obsession and who didn’t reorient their life around their craft. I did not take Jim seriously nine years ago. That was a mistake.

But Jim was wrong, too.

Earlier this year, the wife of my partner and investor, Eben Pagan, sent an email that changed my life. She wrote:

Every leader Eben invests in works with me to support the whole system working and succeeding. So we offer it as a contribution to your family dynamic feeling smoother and softer. When you and Sheena know how to find each other in difficult times, it only adds to your success in business.

How does next week Tuesday sound?

Much love,

Annie

Since then, I’ve talked weekly with Annie Lalla, who happens to be a brilliant relationship coach, and those conversations have shown me that Jim was also wrong. One day as I was telling Annie about the difficulties of parenting, I realized that what I was actually doing was resisting being a parent. When challenges came up I thought to myself, “Arghh. Why is this happening? I can’t believe I have to deal with this.” I also realized that I had unconsciously accepted that I wasn’t ever going to be a great parent.

As I shared these thoughts with Annie—thoughts I hadn’t even been aware of just minutes prior—she asked me, “Why can’t you do both?”

“Here we go,” I thought to myself. “Where do I start?” I told her about Jim. I told her about the biographies. I told her about the low point in our marriage when I was trying to have it all. I told her that I didn’t really think it was possible.

But she pushed back. “That was in the past! You aren’t the same as you were five years ago. You have new experiences and lessons learned. And society isn’t the same either. There are new tools there, too. Right?”

“Yes.”

“You are someone who likes to pioneer, right?”

“Yes.”

“Society needs pioneering men like you who find new ways to balance and blend career and family. You can be a role model for the next generation.”

In the movie Inception, a group of agents plant thoughts in people’s heads while they’re dreaming. Those thoughts can grow, change the whole constellation of that person’s beliefs, and alter their decisions when they awaken. At that moment, I felt like I had been incepted.

Annie’s suggestion took hold. Nine years after that conversation with Jim, knowing what I know now, I began to believe I could do it differently. But I wondered how.

The answer I’ve come to for myself is what I call the Snowball Principle.

The Snowball Principle And How To Have It All

The Snowball Principle is the idea that we can have it all if we’re willing to:

Get the fundamentals right FIRST and make them non-negotiable.

Have Big, Hairy, Audacious Goals (BHAGS), but be patient with them.

Replace all-or-nothing sprints with a marathon mentality.

It’s the idea that if we do the right things consistently over a long period of time, the future we want becomes more and more inevitable because our actions compound upon one another.

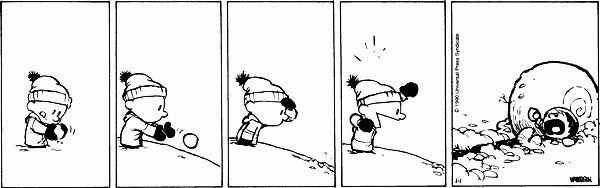

Just as a small snowball being rolled down the hill slowly picks up snow with each rotation and becomes a huge one:

Or how a tiny domino can eventually knock over a huge one if you give the momentum time to compound upon itself:

With both the snowball and the dominoes, the ending is inevitable.

One of my role models for the Snowball Principle happens to be one of my closest friends since high school. Cal Newport and I founded a company together when we were 16 years old. Over the years, one thing I’ve noticed about Cal is that he is incredibly consistent in what he commits to.

Cal wrote his first book while he was in college, and he has devoted a small amount of time to writing almost every weekday since then. As a result, over the last 16 years, he has:

Written six bestselling books

Earned a computer science Ph.D. from MIT

Obtained a tenured professorship at Georgetown

Become a father of three

But wait, here’s the real clincher: He does all this while consistently shutting off work at 5 p.m. daily and taking weekends off.

I remember being skeptical of Cal’s approach when we were in our 20s. Why not just jump 100 percent into one thing? Why shut down work at 5 p.m. when you don’t have kids and you can fill up that time? I remember Cal once saying that his brain would only allow him to do about five hours of truly deep work per day. The first word that came to my mind was “lazy.”

After seeing Cal’s results compound, I’ve turned from a skeptic into a believer. After observing my own body’s energy when I do deep and focused work, I discovered that 5 hours per day is about right.

The chart below explains what I missed about the power of Cal’s approach. In the beginning of earning compound interest, you don’t see the benefits of compounding. Your results in the beginning are tightly correlated with your effort, but, by the end, the interest is doing almost all of the work for you.

With patience and consistency, we can have it all.

Here is a breakdown of each of the components of the Snowball Principle…