The Founders Of The World’s Five Largest Companies All Follow The 5-Hour Rule

Author’s Note: This article was written over 60 hours with love and care using the blockbuster mental model.

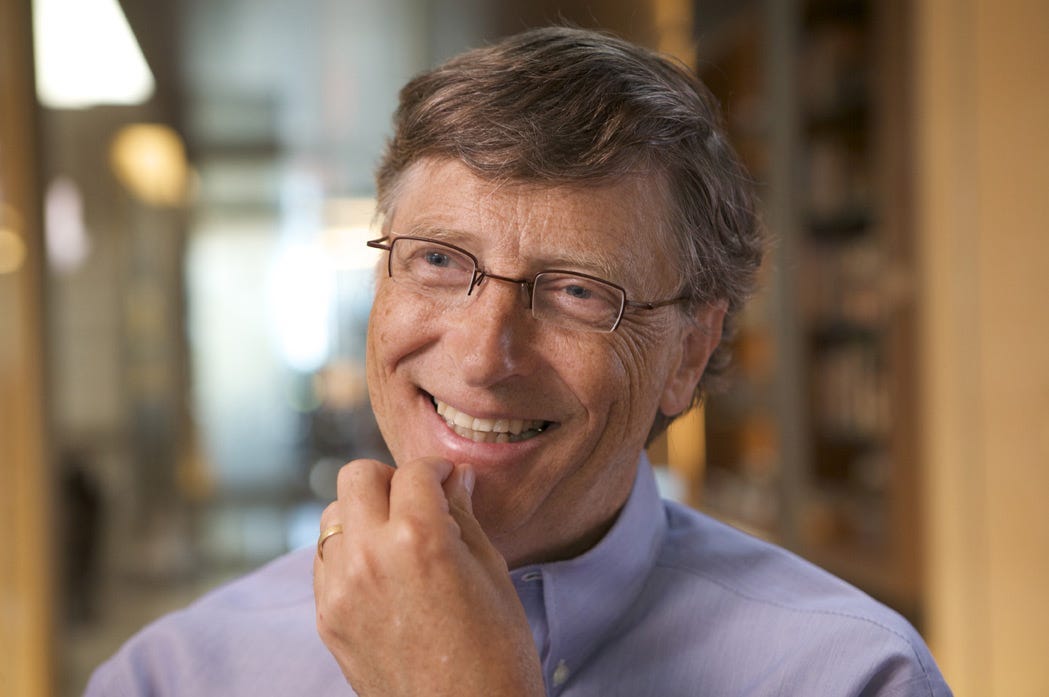

Bill Gates. Steve Jobs. Warren Buffett. Jeff Bezos. Larry Page. They are all polymaths too.

The founders of the five largest companies in the world—Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Warren Buffett, Larry Page, and Jeff Bezos—all share two uncommon traits. After studying self-made billionaires for many years now, I believe that these two traits are responsible for a lot of their wealth, success, impact, and fame. In fact, I put so much faith in these two traits that I’ve used them in my own life to start companies, be a better writer, be a better husband, and achieve financial security.

Here are the two traits:

Each of them is a voracious learner.

Each of them is a polymath.

Let’s unpack these two terms, and learn a few simple tips for using them in your own life.

First, the definitions. I define a voracious learner as someone who follows the 5-hour rule, dedicating at least five hours per week to deliberate learning. I define a polymath as someone who becomes competent in at least three diverse domains and integrates them into a skill set that puts them in the top 1% of their field. If you model these two traits and take them seriously, I believe they can have a huge impact on your life and really accelerate your success toward your goals. When you become a voracious learner, you compound the value of everything you’ve learned in the past. When you become a polymath, you develop the ability to combine skills, and you develop a unique skill set, which helps you develop a competitive advantage.

By Bill Gates’ own estimate, he’s read one book a week for 52 years, many of them having nothing to do with software or business. He also has taken an annual two-week reading vacation for his entire career. In a fascinating 1994 Playboy interview, we see that he already thought of himself as a polymath:

PLAYBOY: Do you dislike being called a businessman?

GATES: Yeah. Of my mental cycles, I devote maybe ten percent to business thinking. Business isn’t that complicated. I wouldn’t want to put it on my business card.

PLAYBOY: What, then?

GATES: Scientist. Unless I’ve been fooling myself. When I read about great scientists like, say, Crick and Watson and how they discovered DNA, I get a lot of pleasure. Stories of business success don’t interest me in the same way.

The fact that Gates considers himself a scientist is fascinating given that he dropped out of college and had spent his whole life in the software industry at that point.

Interestingly, Elon Musk doesn’t consider himself a businessman either. In this recent CBS interview, Musk says he thinks of himself as more of a designer, engineer, technologist, and even wizard.

The list goes on. Larry Page has been known to spend time talking in depth with everyone from Google janitors to nuclear fusion scientists, always on the lookout for what he can learn from them.

Warren Buffett has pinpointed the key to his success this way:

Read 500 pages every day. That’s how knowledge works. It builds up, like compound interest.

Jeff Bezos has built his whole company around learning on a massive scale via experimentation and has also been an avid reader his whole life.

Finally, Steve Jobs famously combined various disciplines and looked at it as Apple’s competitive advantage, going so far as to say:

Technology alone is not enough. It’s technology married with the liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields the results that makes our hearts sing.

And, of course, the founders of these five companies aren’t the only massively successful individuals who share these two traits. As I’ve written about before, if we expanded the list to a sample of other self-made billionaires, we quickly see Oprah Winfrey, Ray Dalio, David Rubenstein, Phil Knight, Howard Marks, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Charles Koch, and many others share similar habits.

Why would some of the busiest people in the world invest their most precious resource—time—into learning about topics seemingly unconnected to their fields, like fusion power, font design, biographies of scientists, and doctors’ memoirs?

Each of them commands organizations of thousands of the smartest people in the world. They’ve delegated almost every task in their life and businesses to the best and brightest. So why have they held on to this intense amount of learning?

After writing several articles attempting to answer these questions, this is what I’ve ultimately come to:

At the highest levels, learning isn’t something you do to prepare for your work. Learning is the most important work. It is the core competency to build. It’s the thing you never delegate. And it’s one of the ultimate drivers of long-term performance and success.

As I came to this realization, I wondered: Why isn’t it obvious that we should all become voracious learners and polymaths throughout our whole lives given that we live in an increasingly complex, rapidly changing, advanced knowledge economy? Why does the average person think of deliberate learning as an optional thing to do on the side?

I think it’s because of three strong messages we’ve all been taught—in school, in college, and in general society—that may have been true in the past, but are definitely no longer true. Here’s how these three lies break down:

Lie #1: Disciplines are the best way to categorize knowledge.

Lie #2: Most learning happens in school/college.

Lie #3: You must pick one field and specialize in it.

These beliefs are so insidious that they’ve destroyed our intuition about learning and knowledge, and they ultimately hold us back from creating the success we want. If we can become aware of them, we can rectify them, just as the most successful people in the world have done.

Lie #1: Disciplines are the best way to categorize knowledge

Our educational system is built on a model that divides knowledge into different subjects—math, reading, history, science. Beginning in kindergarten, we get the message that these subjects are best learned individually.

We even break these subjects down further into smaller fields of study—economics, for instance, breaks down into microeconomics and macroeconomics. This paradigm of breaking fields down and teaching them separately is called reductionism. Though it’s still the standard in our society, it’s actually starting to change in more progressive countries.

Reductionism has big benefits. Within tightly-knit fields, ideas travel quickly and efficiently because everyone belongs to the same culture and speaks the same language. It is easier to investigate the pieces of a system rather than a whole complex system. The paradigm has led to many important discoveries.

But one key disadvantage of reductionism is that the connections between fields become obscured. This results is what is known as “negative learning transfer,” which is when learning one thing makes it harder to learn something else because the concepts we’ve learned are so strongly tied to the specific field of study. If you’ve ever gotten tripped up while trying to learn a second language whose rules of grammar, word order, tense, or pluralization don’t match those of your native language, you’ve experienced a negative learning transfer.

Another weakness is that people outside of a specialized field cannot easily grasp what’s happening inside it. Picture one neurosurgeon talking shop with another. No problem, right? Now picture a neurosurgeon trying to explain advancements in brain surgery to a graphic designer. Each field has its own language and culture, and so unique insights in one field aren’t applied to another even though they often could and should be. This leads to echo chambers.

In reality, what we learn is strongly attached to the context we learn it in. Take exercise. Until very recently, I used to circle my gym’s parking lot for five minutes in order to find the closest parking space. Instead of taking the stairs, I took the elevator up to the locker room. And do you know what machine I used? The stair climber! This is just one of many examples where seemingly obvious transfers fail to happen.

Biologist James Zull explains why learning transfer is so complicated in his book, The Art of the Changing Brain:

Often we don’t have the [neural] networks that connect one subject with another. They have been built up separately, especially if we have studied in the standard curriculum that breaks knowledge into parts like math, language, science, and social science.

Because we are not taught to see the common roots of all knowledge, we don’t see their interconnectedness.

Elon Musk feels so strongly that our educational system fails to teach children these “common roots” that he has created his own school and put all of his kids into it. In a fascinating interview that Musk did on Chinese television, he shares why he made the decision and challenges the paradigm of reductionism:

It’s important to teach to the problem, not to the tools. Let’s say you’re trying to teach people about how engines work. A more traditional approach would be to say, ‘We’re going to teach all about screwdrivers and wrenches, and you’re going to have a course on screwdrivers and a course on wrenches …. That’s a very difficult way to do it.

A much better way would be to say, ‘Here’s the engine. Let’s take it apart. How are we going to take it apart. Oh. We need a screwdriver. That’s what the screwdriver is for. We need a wrench. That’s what the wrench is for.

And then a very important thing happens. The relevance becomes apparent.

Over the years, I’ve learned that there is a deeper way to categorize knowledge, a way to learn fundamentals that apply across all fields and teach skills that stay with a person for life. These fundamentals are called Mental Models, and I’ve written extensively about them in this article and in my Mental Model of the Month Club.

Let’s look at just one mental model, called “stress and recovery.” Going back to the example of exercise, the phenomenon of stress and recovery is the reason exercise makes us stronger: it temporarily stresses our muscles and cardiovascular system past their current capacity, and they rebuild themselves during recovery. With this mental model in mind, we can look for it in other areas and across fields. For example, it explains why certain types of difficult experiences can help us become mentally strong. In the psychology world, this is known as post-traumatic growth. In the social psychology world, these types of difficult experiences are called diversifying experiences. In adult development, they’re referred to as optimal conflict. With these examples, we can see how the same underlying mental model is given a different name in different fields of application.

Mental models are the invisible networks of ideas that connect disciplines together.

They are what many of the world’s top learners and polymaths use to get ahead in our knowledge economy.

TRUTH: It is just as important to categorize knowledge by mental models as it is by subject because mental models underlie and connect subjects.