We’re In A Productivity Crisis, According To 52 Years Of Data. Things Could Get Really Bad.

Author’s Note: I spent over 500 hours researching and writing this article. Those 500 hours were spent reading through dozens of books/studies in 10+ fields (history, economics, technology, philosophy of science, manufacturing, management, sociology, investing, innovation). I spent so much time because the topic was both much more interesting and complicated than I originally thought. And, as is the case with most of my writing, I use the blockbuster philosophy. This means I don't click publish unless I think it is one of the best articles that has been written on the topic.

As a result of going through the research process, I will never think about productivity in the same way. What I learned blew my mind over and over, and I hope it does the same for you as the reader.

The most important, and indeed the truly unique, contribution of management in the 20th century was the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the manual worker in manufacturing.

—Peter Drucker

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. The “Great Boom” was supposed to last.

From 1870–1970, there was an incredible 50x increase in the productivity of the average manual worker. Let me break that down so it really lands for you like it did for me:

50x Increase: Imagine getting 50 hours of work done in one hour. Or imagine doing the work of 5o people by yourself.

On Average: We’re not just talking about a 50x increase for the most ambitious, smartest manual workers. We’re talking about all manual workers.

To put the profundity in context, the “Great Boom” is one of the most amazing and under-appreciated events in economic history. The chart below captures its magnitude and uniqueness:

To more deeply appreciate this shift, consider the following:

This is a unique event in all of history. “Modern humans first emerged about 100,000 years ago. For the next 99,800 years or so, nothing happened… Then — just a couple of hundred years ago—people started getting richer. And richer and richer still,” states Economist Steven Landsburg.

Before it happened, the average American lived on about a dollar a day (in today’s dollars). “Before 1750, almost nowhere in the world were living standards something that we would call anything but miserable and poor,” according to economic historian Joel Mokyr. Economist Steven Landsburg adds, “Almost everyone lived on the modern equivalent of $400 to $600 a year, just above the subsistence level.”

Before it happened, day-to-day life was brutal. “In 1870, farm and urban working-class family members [in the United States] bathed in a large tub in the kitchen, often the only heated room in the home, after carrying cold water in pails from the outside and warming it over the open-hearth fireplace,” according to economic historian Robert Gordon.

Bottom line: The people alive between 1870–1970 experienced unprecedented change. Now, imagine being an adult in 1970. Think about how you’d see the world…

Looking Back From 1970, You See A Wondrous Productivity And Lifestyle Boom

Below are a few examples of the changes and their implications. Of particular note are:

The shortening of the workweek from 68 hours to 40 hours.

The removal of child labor

Wondrous technologies in the most important parts of life

100x increase in worker safety

#1: Shortening of the workweek from 68 hours to 40 hours

This means parents could be home with their children more, spend more time with friends, and spend more time on their mental and physical health.

#2: Removal of child labor

Many children started work at 4 years old and worked 12-hour days doing intricate work that benefitted from having small hands or dangerous work that required working in small places adults couldn’t reach. Around the same time that children were removed from factories, they were put in schools. As a result of this shift and an explosion of free public education, illiteracy went down 20x while school enrollment doubled. As a result, the seeds were planted for an educated workforce and society.

#3: Wondrous technologies in the most important parts of life

We see inventions like cars, elevators, automobiles, plumbing, heating/cooling, penicillin, and electricity. Collectively, these make life more safe, mobile, comfortable, and urban.

#4: 100x increase in worker safety

Worker safety means things like protection from accidents, disease, pollution, fires, etc. along with protection in the case of injury. As an example of the extreme shift that happened, 19th century US Steel workers had a one in seven chance of being killed before 50 and a one in three chance of being disabled, according to economic historian Brad Delong.

In addition, people started receiving benefits like health care, paid vacations, social security, and disability protection. This gave people a new level of safety knowing that they would be taken care of rather than their life being destroyed forever if something went wrong.

With these huge gains, it was no wonder that…

Looking Forward From 1970 You Could Envision Utopia

Given the massive change between 1870–1970, looking forward from 1970, you could confidently see the potential for another 50x boom because of the computer revolution and digital knowledge work.

The promise was that what machines were for our bodies, computers would be for our brains… except on steroids. Furthermore, rather than sending products/services around the world on planes and ships, we could send bits across the world instantly at zero cost.

The shift to digital knowledge work made it possible to imagine a knowledge work revolution that could eclipse the manual worker productivity revolution:

30-hour work weeks with work being voluntary for many

Freedom over what, when, where, how, and with whom you work

Passion-fueled work that is creative and curiosity-filled

Meaningful work that connects us to other humans and purpose

Amazing technologies like living forever, all-powerful artificial intelligence, flying cars, etc

For example, in 1970, MIT AI pioneer Marvin Minsky predicted in Life Magazine that:

In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being.

Not only that, in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt supported and the Senate passed a 30-hour workweek bill. Though, it ultimately fell through. In 1956, Richard Nixon predicted a 32-hour workweek in the “not too distant future.”

In other words, if you were prone to optimism and living in 1970, you could imagine a work utopia in the 21st century.

But something odd happened…

Bizarrely, In 1970, Lots Of Things Started Going Downhill

The simple claim that in modernity ‘everything goes faster and faster’… is transparently false.

—Sociologist Hartmut Rosa, Social Acceleration

At the exact point you’d expect things to go from good to great, bad things started happening.

For starters, the productivity growth rate decreased significantly (known as the productivity paradox):

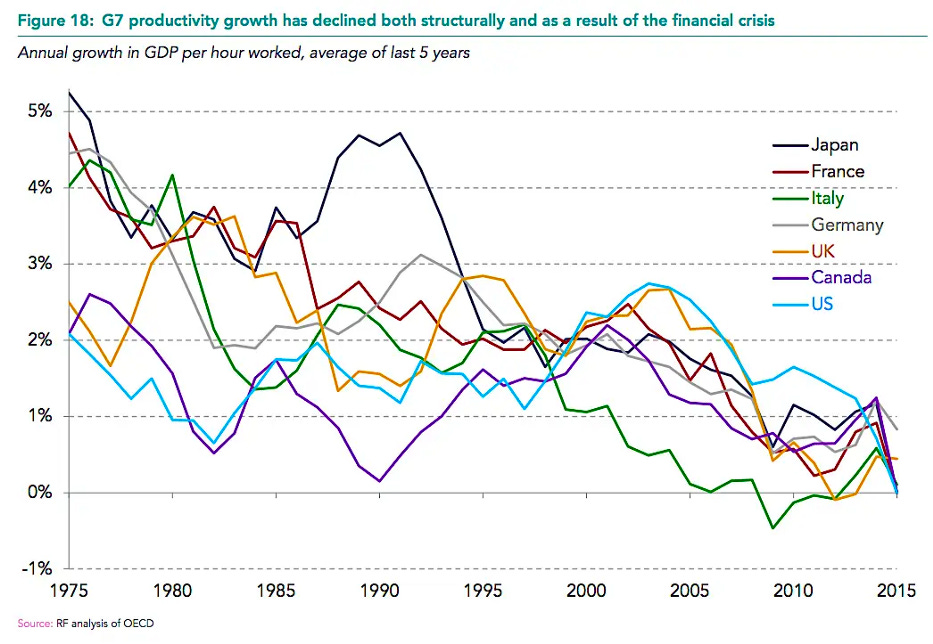

This phenomenon happened worldwide, not just in the United States. The following chart of GDP per hour (output per hour) growth captures the global phenomenon more precisely…

At the same time that productivity overall was increasing (even if the growth rate dropped), most of the productivity gains went to the top earners while the middle class stagnated. This is known as the Great Decoupling…

This stagnation is a big deal. When you stop believing that your kids will have a better life than you, you stop believing in the “American dream.” And according to a 2022 survey of 1,300+ people in 19 countries, 70% of survey respondents believe their children would be worse off financially—a significant increase compared to previous years.

Other examples of stagnation include:

The price of energy is stagnant rather than decreasing.

Transportation isn’t moving faster than decades ago (i.e., cars & planes).

Biotech innovation is ⅓ the rate compared to 20 years ago.

Healthcare and education costs are increasing significantly without a commensurate increase in results.

The average lifespan in developed countries is stalling.

Agricultural innovation has decreased significantly for the first time in nearly a century.

Large construction projects are more expensive and take much longer.

These before-and-after pictures of the physical world further capture what hasn’t changed in ways that words can’t:

In fact, the list of things going haywire from the early 1970s until now is so large and odd that there is an entire research-based, well-known site devoted to it called WTF Happened In 1971?.

To summarize: We have this unprecedented 50x rise in manual work productivity between 1870 and 1970. Then, at the exact time you’d expect things to have another 50x boost because of the computer revolution, things start slowing down.

The big implication: Ultimately, the productivity paradox points to a gaping hole in our general understanding of one of humanity’s greatest achievements—The Great Boom between 1870–1970. And, it’s more important than ever that we fill that hole now if we want it to dramatically improve everyone’s lifestyle and well-being in the future. Because, if we don’t, things could go from not good to plain bad…

The Productivity Paradox May Be The Most Important Societal Problem We Face

The only way to raise living standards over the long term is to raise productivity.

—Ray Dalio

The Productivity Paradox is not an idle curiosity.

It’s life-changing and relevant for all of us. It impacts our lifestyles, careers, government, society, and economy at fundamental levels. Even if we don’t realize it, the effects of the productivity paradox already touch our lives in many ways…

For example, if societal and individual productivity growth continues to plateau or decline, it could mean war, generational lifestyle stagnation, our currency going to zero over time, the rise of communism, environmental catastrophe, and stalling of innovation.

Unfortunately, these aren’t wild predictions. They are extrapolations of what’s already happening now and backed up by history. This is not the first productivity paradox ever, so we don’t have to completely guess what the implications might be.

Let me expand on each potential future to let the severity sink in…

War. Less productivity means a smaller pie for everyone to split. Escalating tension between the haves and have-nots could devolve into conflicts (civil war, coup, etc). Famous investor and student of history Ray Dalio summarizes the situation: “When wealth and values gaps are large and there is an economic downturn, it is likely that there will be a lot of conflict about how to divide the pie.”

Currency That Goes To Zero. Government debt will continue to skyrocket (less productivity creates less tax revenue). And if history is a teacher, governments will print more and more money to pay off that debt, which will cause more and more inflation, which devalues the currency. In a surprisingly extreme prediction, one of the world’s most successful and oldest (nearly 100 years old) investors Charlie Munger predicts (40 seconds into this video) that the US currency will go to zero in the next 100 years and shares many historical precedents of where extreme inflation led to the demise of democracies.

Rise Of Communism. In difficult times, there is a backlash against capitalism and democracy and a rise in socialism. In a fascinating clip on the Lex Fridman podcast, Harvard-trained economist Richard Wolff shares the surprising stat that there was a huge rise of the Communist party. In other words, the more growth stalls, the more people there are calling for revolution, not just reform. In fact, one of the great management researchers of all time Peter Drucker argues that the prosperity from the manual work productivity revolution was the reason that the United States did not become Communist during the Great Depression.

Environmental Catastrophe. The way we use resources to create energy is already unsustainable. Pollution will eventually destroy our world if we don’t learn how to create more energy and goods with dramatically fewer resources.

None of these futures are guaranteed to happen. But they are serious scenarios discussed by many of the smartest people in the world, and that alone is concerning.

Bottom line: This state of affairs is not sustainable. The consequences are predictable based on history. And those consequences have been already playing out and could get much worse.

There comes a point at which one has to declare a state of urgency, if not an emergency. And that moment is now.

The productivity growth rate is a fundamental input that impacts lots of other things we care deeply about.

The productivity paradox is arguably the most important puzzle that will determine the future of our society and our careers. We are in a purgatory between hell and heaven. Hell of escalating conflict and stagnation. Heaven of a work utopia.

Given the importance of productivity, you would expect a few things to happen:

It would be the headline of every major newspaper.

World leaders would be constantly talking about it.

Knowledge workers and companies would go all out increasing productivity.

Yet, not only is productivity growth rate not talked about, but there is a huge backlash against it…

Inside The Productivity Backlash

At first, I thought the idea of a backlash against productivity was ridiculous. I wondered, how can someone be against the idea of getting more of what they want with less cost? But, as I read books and articles that I actually disagreed with at first, I became aware of the compelling points I could not ignore. I realized that I had only been looking at productivity through my own lens rather than empathizing with other people’s lived experiences.

Below is a summary of the core reasons there is a backlash against productivity:

More productivity doesn’t mean less work for employees. Workers feel pressured to work harder even as they become more efficient.

Workers aren’t receiving the gains from their increased productivity. The gains in productivity are not redistributed to workers in a way they feel is fair.

Hustle culture isn’t appealing. Many people aren’t excited about making every work moment more productive and filling every free moment with more work.

As tasks are systematized, they can become boring and mechanical. Extreme specialization may be more efficient, but it can lead to simple repetitive work that is boring. Many associate productivity with being overly structured or mechanical. For example, one person I talked to for this article said that one of his bosses once said to him, “When you walk in the door, I only want everything below your neck.”

Many are jaded by failed productivity experiments. Many productivity experiments fail and even make things worse or more frustrating (ie — lifeless call center agents reading empty scripts).

Increased overall productivity has directly hurt certain groups. Rapid changes in society because of productivity growth inevitably disadvantage people who live in certain regions, who work in specific industries and professions, or who come from certain cultures. For example, outsourcing America’s manufacturing turned many company towns into ghost towns that now suffer from brain drain, falling property prices, poverty, and addiction.

While there are many signs of productivity backlash, below are some of the most apparent examples.

For one, there is now a whole genre of anti-productivity bestsellers…

For example, in Four Thousand Weeks, author Oliver Burkeman argues:

The modern discipline known as time management—like its hipper cousin, productivity—is a depressingly narrow-minded affair, focused on how to crank through as many work tasks as possible, or on devising the perfect morning routine, or on cooking all your dinners for the week in one big batch on Sundays.

We can also see the tension between pro-productivity and anti-productivity culture in these two opposing memes about the same incredibly destabilizing event of Covid:

For many, productivity culture is a tool that the ruling class uses in the context of capitalism to get as much work out of workers as possible.

For example, How Millennials Became The Burnout Generation, which was read over six million times, makes the case that capitalism is the root cause:

Until or in lieu of a revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist system, how can we hope to lessen or prevent—instead of just temporarily stanch— burnout? Change might come from legislation, or collective action, or continued feminist advocacy, but it’s folly to imagine it will come from companies themselves. Our capacity to burn out and keep working is our greatest value.

The late anthropologist David Graeber, author of Bullshit Jobs, which also started out as an article with millions of views puts the blame on the ruling class:

The answer clearly isn’t economic: it’s moral and political. The ruling class has figured out that a happy and productive population with free time on their hands is a mortal danger. (Think of what started to happen when this even began to be approximated in the sixties.) And, on the other hand, the feeling that work is a moral value in itself, and that anyone not willing to submit themselves to some kind of intense work discipline for most of their waking hours deserves nothing, is extraordinarily convenient for them.

Finally, this viral tweet below from former US Secretary of Labor Robert Reich encapsulates a growing sentiment against wealth. It implies that wealth cannot be achieved by entrepreneurs and innovators who start from nothing and who become more innovative by innovating amazing products and services that customers love:

As I spent more time considering all of this backlash, I felt like I was shifting between two realities. Sometimes I felt like people were unfairly judging productivity. Other times, I wondered, “Wow! Maybe there are enough things wrong about productivity that there is a deeper structural issue culturally or economically that I’ve been too biased to see.” (More on how I ultimately synthesized everything later in the article)

Bottom line: It is now cool to publicly be against getting more of what you value with fewer and fewer resources. For many, productivity has become a bad word from bad people (wealthy people) from a bad system (capitalism).

Not only are we having a backlash against productivity, but the productivity paradox is also almost completely hidden from day-to-day conversation or news…