While Everyone Is Distracted By Social Media, Successful People Double Down On An Underrated Skill

This career skill will change the way you think about reading.

Author’s Note: This article was written over 60 hours with love and care using the blockbuster mental model.

The information we consume matters just as much as the food we put in our body. It affects our thinking, our behavior, how we understand our place in the world. And how we understand others.

—Evan Williams, Co-Founder of Twitter and Medium

Right now, somewhere out in the world is a paragraph, chapter, or book that would change your life forever if you read it. I call this kind of information “breakthrough knowledge,” and mastering the ability to find breakthrough knowledge in our era of information overload is one of the most important skills we can develop.

We’ve all had breakthrough experiences. A phrase that a parent, mentor, or teacher said that stuck with us and changed everything. A “quake” book that shook us to our core.

Warren Buffett’s quake book, for example, was The Intelligent Investor, which he read when he was 19. This book cemented the core of the investment philosophy Buffett would use throughout his career. Elon Musk’s quake book was The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which he said helped him ask bigger questions, and therefore think about addressing larger problems in the world. My most recent quake book was Poor Charlie’s Almanack, written by self-made billionaire Charlie Munger. This was the first book that exposed me to mental models. Learning and applying mental models has been so impactful that I recently created the Mental Model of the Month Club.

Quake books are rare, but one is worth a thousand merely good books. A breakthrough knowledge experience might only last a few minutes, but its effect can last a lifetime. It is the ultimate form of learning leverage.

Now, imagine having a breakthrough knowledge experience once a year rather than once a decade. Or perhaps twice a month rather than once a year. It would change everything, and it’s possible.

Given the power of breakthrough knowledge and the difficulty of finding it, one of the most fundamental questions we all need to ask ourselves is:

How do we use the limited time we have to find breakthrough knowledge in a sea of distractions?

My interest in this question is personal. As someone who has read thousands of books across disciplines, I’ve asked it repeatedly throughout the years. There are hundreds of books scattered among my bookshelves, Amazon shopping cart, Kindle library, and Audible wish lists that I’d love to read, but don’t have time for—a veritable “infinite playlist.”

Over time, I’ve developed a unique approach to handling information overload, based on my own experience and observing how many of the world’s top entrepreneurs and leaders learn (including Elon Musk). But before we jump into that approach, we first need to understand the problem. As inventor Charles Kettering once said:

A problem well-stated is a problem half-solved.

(Side note: several people have jumped into the comments on the original article and shared their favorite quake book or their biggest strategy to find breakthrough knowledge. I’d love to hear from you too, and I read every comment.)

The Four Horsemen Of The Info-Apocalypse

Although we think of information overload as one big problem, it actually consists of four problems that are each getting exponentially worse, and that together add up to one big crisis. This crisis risks making us collectively dumber instead of more intelligent, and tearing us apart instead of bringing us together. The crisis goes by many names, but the one that I think is most apt is Info-Apocalypse.

The four problems that make up the Info-Apocalypse are:

Content Shock

Echo Chambers

Constant Distraction

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out)

Info-Apocalypse Problem 1: Content Shock

A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention …

―Herbert A. Simon

With the advent of online publishing and social media, the amount of knowledge available to us is expanding so fast that none of us can possibly keep up. Meanwhile, more content is added to the pile every second of every day. The gap between this total collective human knowledge and our time to consume it grows larger every second.

The problem: Much new information and many new skills we could learn are out there, but they’re so buried that we don’t even know they exist.

Info-Apocalypse Problem 2: Echo Chambers

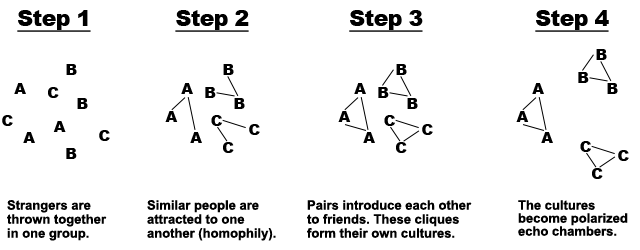

As groups grow in size, they become less stable and more diverse, eventually fracturing into subgroups. One of the most identifiable examples of this phenomenon is religion. Judaism grows until it branches into several different sects, one of which breaks off into Christianity. Christianity grows, then branches into Catholic and Protestant. Protestantism grows, then branches into Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran, and so on.

This happens in every growing field, discipline, and community. Each new group develops its own language and culture. While this improves communication inside the group, it makes it harder for knowledge to travel in or out, because it must be linguistically and culturally translated first.

Each group develops an identity based, in part, on how it’s different or better than other groups. These conceptual walls between groups lead to polarization and prejudice. It’s easy to see this happening in religion and politics, but it happens in all fields: Artists who become too business-oriented are considered “sellouts.” Business executives often look down on academics as too theoretical and not practical. Many people in the hard sciences don’t even consider social sciences an actual science. Academics who write popular books are considered to be less serious researchers.

The problem: Each group lives in its own echo chamber, which it believes is the “true” reality, and it fights to maintain this belief by demonizing other groups. And in an age of social media and targeted personalized content, these echo chambers become even more insular (see The Filter Bubble for more on this), as we’re exposed to less and less information outside our own chosen groups.

Info-Apocalypse Problem 3: Constant Distraction

Interviewer: You said that this is a time for soul searching in social media businesses and you were part of building the largest one. What soul searching are you doing right now on that?

Chamath Palihapitiya: I feel tremendous guilt … I think we all knew in the back of our minds, even though we feigned this whole line of, “There probably aren’t any really bad unintended consequences.” I think in the back, deep, deep, deep recesses of our minds, we kind of knew something bad could happen.

About five years ago, I interviewed the founder of Meetup. Somehow we got talking about social media news feeds, and he said something that has stuck with me:

If you think this is addictive, just wait until five years from now.

Well, it’s five years later, and my relationship with mobile devices, the Internet, and social media has changed in a scary way. As time goes by, I’ve become extremely vigilant—downloading Chrome extensions like Crackbook Revival and Newsfeed Eradicator), deleting all social media apps from my phone, adding a password that only my wife has so I can’t download new apps—and it still feels like I’m losing the battle.

I can swear off Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube as much as I’d like, but each of these is also where I work to build my business. I manage Facebook Groups with over 300,000 members. I buy Facebook and Google ads and promote new articles on Facebook.

I’ve tried blocking YouTube, but there are so many high-value educational videos there that I decided to turn it back on. Even though I work from home, when I open my computer, it feels like I’ve set up shop in the middle of a busy bazaar.

Marketers, software developers, and hackers are gaining unprecedented access to data on human behavior. They use this information to master the science of capturing people’s attention and addicting them to their product. Billions of dollars are spent every year toward these ends. They have developed business models based on advertising—or spreading misinformation—to get the maximum number of clicks for the least amount of effort.

To complicate things further, in the not-too-distant future, a significant percentage of humanity may be looking at life through augmented virtual-reality glasses or contact lenses, which will make the problem even worse.

The problem: Our physical and virtual environments are surrounded by more and more content—whether editorial, advertising, or “fake news.” This content is marketed specifically to our own inclinations, which proves a powerful distraction that can keep us from pursuing more useful information or our own goals.