While Most People Fight To Learn “In-Demand” Skills, Smart People Are Learning Rare Skills Instead

Author’s Note: This article was written over 60 hours with love and care using the blockbuster mental model.

When self-made billionaire investor Ray Dalio wanted to understand changing world events, he didn’t just look at the latest news. He became an amateur historian and spent months looking back at cycles going back hundreds of years—something almost no one else does.

When Bill Gates wanted to grow Microsoft in the early 1990s, he didn’t just study the latest industry news and business books. He studied science. A 1994 interview is telling:

Interviewer: Do you dislike being called a businessman?

Bill Gates: Yeah. Of my mental cycles, I devote maybe 10% to business thinking. Business isn’t that complicated. I wouldn’t want to put it on my business card.

Interviewer: What, then?

Bill Gates: Scientist.

Similarly, when Elon Musk thinks about what CEOs need to know, he doesn’t put business skills near the top of his list. Instead, he says:

The path to the CEO’s office should not be through the CFO’s office, and it should not be through the marketing department. It needs to be through engineering and design.

—Elon Musk

What’s going on here?

How is it possible that three of the top investors and innovators in human history say that business skills aren’t the key to business success? It’s like saying the key to parenting isn’t parenting skills. Or that the key to gardening is not gardening skills.

It makes you wonder:

What do they see differently about selecting skills to learn than others? Or are these just quirky people who enjoy exploring their curiosities?

To answer this question, we need to think about what a quirk is. For something to be a quirk, it needs to be unique and inconsequential.

What I found is that the opposite is true here:

Dalio, Gates, and Musk think the same. Although they have unique quirks on the surface, at a deeper level, they all think differently in the same way (more on this later).

They are not the only ones. Nearly all top .0001% innovators and investors share the same thinking pattern.

Their “quirk” is one of their keys to success. Many of them have sworn by this (more on this later).

What I will argue in this article is that Elon Musk, Ray Dalio, Bill Gates, and other top performers have an incredibly unique and effective approach to selecting skills to learn that we can all apply to our own lives.

This is important because skill selection is the Archimedes’ lever of learning. Or as Tim Ferriss succinctly says:

Material beats method.

—Tim Ferriss

With poor skill selection, we drown in the sea of humanity’s knowledge. All of the effort we spend learning and applying what we learn is muted at best or wasted at worst. On the other hand, if we master the ability to select skills, then just 100 hours of learning could have a life-changing impact. The difference between the two harkens back to this famous Stephen Covey quote:

If the ladder is not leaning against the right wall, every step we take just gets us to the wrong place faster.

—Stephen Covey

To connect the dots of Gates, Musk, and Dalio’s unique approach to skill selection, it’s critical to look at a few more dots—this time from Warren Buffett, Peter Thiel, Jeff Bezos, and Howard Marks…

What Self-Made Billionaire Investors And Entrepreneurs Understand That Others Don’t

In 2010, I made two of the most consequential learning decisions in my career.

First, I decided to learn from the world’s top investors based on the premise that we are all investors and that the core mental models that financial investors use to make investments could be used in my life as well. After all, we all invest our time and money into skills, relationships, projects, and jobs that we hope will have a big payoff in the future.

Second, I decided to raise the bar of who I learn from. After reading Fooled by Randomness, I realized that luck plays a much larger role in most people’s success than I had thought and that most successful people care to admit. To select people who were successful primarily because of skill, I added the following filters:

They are in the top .0001% of performers. Because I was studying investing, this meant that they were self-made billionaires. In other words, they had been able to turn their knowledge into incredible real-world success, and they weren’t born with silver spoons in their mouths.

They are not one-hit wonders. In order to narrow down those who were successful primarily because of skill, I narrowed down the list to those who had a multi-decade track record of increasing success. They weren’t just in the right place at the right time one time in their life.

They’ve extensively and eloquently shared their lessons with the world. Next, I narrowed down the list to people who have written books, have been interviewed extensively, or shared their thoughts publicly in other ways so I could learn from them.

They made their money ethically. Not by rent-seeking or breaking the law. And often have been very philanthropic.

When I added these filters, I immediately saw the skill selection pattern. Sometimes, removing the noise is everything. For example, it is hard to see the letter hidden within these dots until you move the dots that are a little more red (for a little fun, put the letter you see in the comments).

Below are a few examples of the dots that connected everything for me:

You want to be greedy when others are fearful. You want to be fearful when others are greedy. It’s that simple.

—Warren Buffet, founder of Berkshire Hathaway

In order to get into the top of the performance distribution, you have to escape from the crowd.

—Howard Marks, founder of Oaktree Capital

The best projects are likely to be overlooked, not trumpeted by a crowd; the best problems to work on are often the ones nobody else ever tries to solve.

—Peter Thiel, founder of PayPal and Facebook

Outsized returns come from betting against conventional wisdom, and conventional wisdom is usually right.

—Jeff Bezos

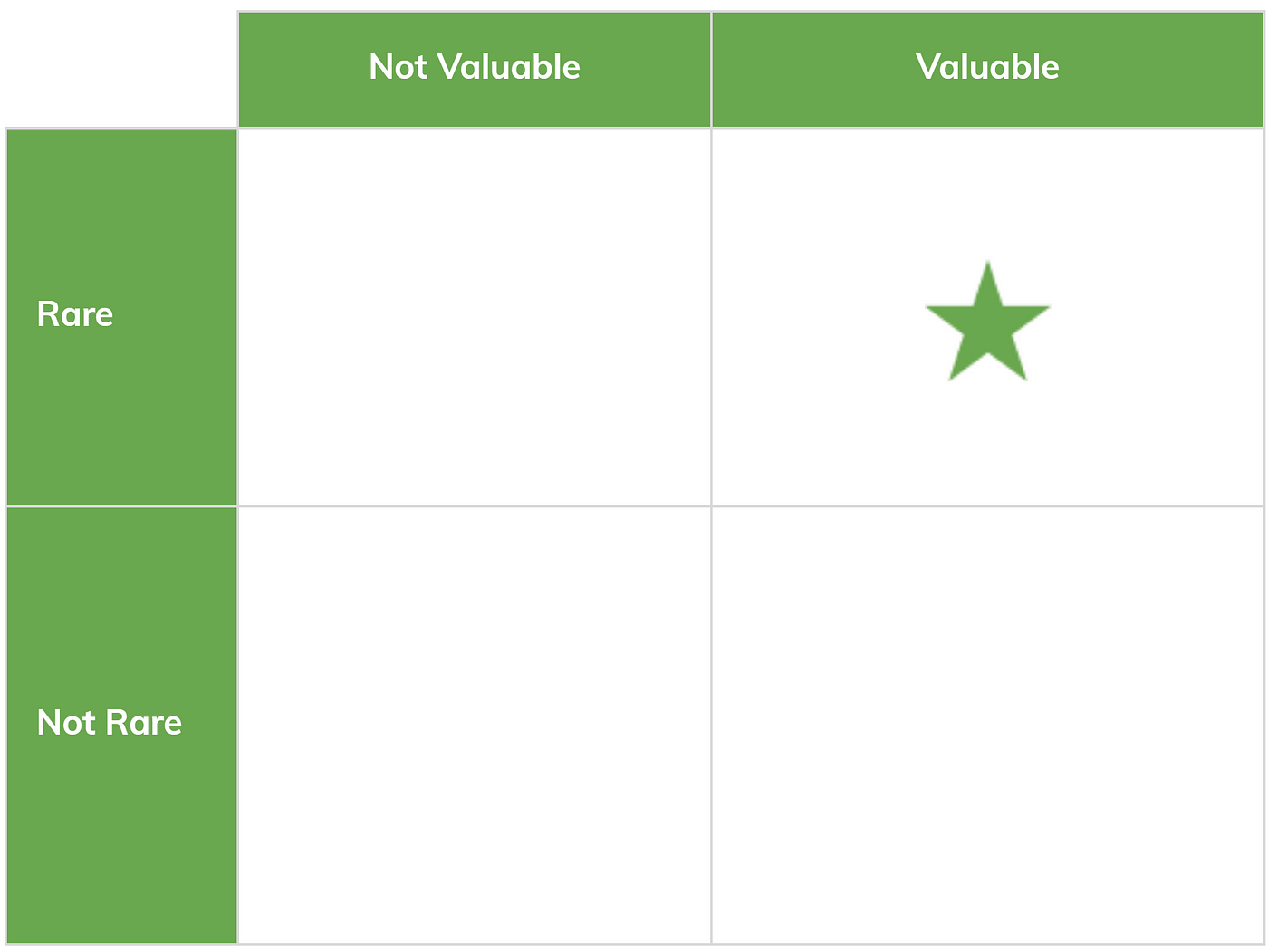

Put simply, each of these innovators and investors is saying you should focus on investments that are rare & valuable. In other words, you should focus on the star below if you want big profits and impact…

I call this model the Outlier Algorithm:

To be an outlier, you need to be a contrarian who is smarter than the market.

Ray Dalio captures the essence of the algorithm with the following quote:

You have to be an independent thinker because you can’t make money agreeing with the consensus view, which is already embedded in the price. Yet whenever you’re betting against the consensus there’s a significant probability you’re going to be wrong, so you have to be humble.

The Outlier Algorithm sounds obvious on the surface, but it’s profound when you go deeper. So, let’s unpack Dalio’s quote…

If you make an investment that everyone already agrees is great, the price will be higher, because more demand increases price. As a result, you will have a lower return on investment. Similarly, if you select a skill that is already popular, learning it won’t give you an advantage over others. Rather, it will simply help you catch up. For example, imagine a recruiter is hiring for a job. If you’re the only person with the skills needed, you can command a premium. If your skills match everyone else, then you’re a commodity.

On the other hand, if you bet against the consensus, you will likely be wrong because the consensus is right most of the time. For example, in financial markets, 90% of professional investors do NOT beat the average of the market. In other words, someone who has spent years investing full-time will regularly underperform amateurs who simply put their money into the S&P 500 Index—a basket of the 500 largest companies listed on US stock exchanges. The same is true for learning. If you want solid returns, simply learning skills everyone says are important is probably a solid bet. But, tautologically, if you want to be in the top 1%, you need to think differently than 99% of others and be right. You can’t expect to follow the herd and somehow beat the herd. Or as Dr. Seuss said even better:

You have to be odd to be number one.

—Dr. Seuss

So the trick is to be right when others are wrong and this isn’t easy.

Looking back on it, the Outlier Algorithm didn’t just help me learn faster, it actually helped me transform at a deeper level…

Applying The Outlier Algorithm To Learning Turned My World Upside Down

The biggest change I noticed right away is that learning hacks that were obviously good now seemed obviously bad. For example…

Reading the latest bestsellers

Staying on top of industry news (that everyone else was following)

Checking social media daily to see what industry influencers were saying (another thing everyone else was doing)

Without knowing it, I had been primarily focused on popularity. My hidden logic was: If others liked this, it must be good.

With the Outlier Algorithm, my logic was inverted: If others liked this, it may be worth becoming familiar with, but I can’t use it to make a big profit or impact.

To drive the point home, ask yourself this question…

How much would you pay for a procedure that would save your life if you were guaranteed to die without it?

Intuitively, you might say you’d give away all your money for it. After all, what matters more than being alive, right?

But, when you add how many other people have a skill to the equation things change. Let’s say everyone in the world knows how to administer the life-saving procedure, and it’s easy to perform.

Now, you’d only pay a few dollars in this case!

The skill is valuable, but not rare, and because it’s missing rareness, others will pay less for it. Furthermore, someone learning the skill will ultimately make less of an impact than they would if they had learned how to perform a life-changing procedure that no one else knew how to do.

With the Outlier Algorithm, my learning sources started to look more like this:

Academic articles

Disciplines outside of my field no one else was even aware of

Licensing proprietary data

Deep relationships with insiders in fields who might not share certain insights publicly

Mental models (abstract value that is harder to value)

After applying these to my life, I noticed some big shifts in my career. As a writer, I could suddenly write about ideas that others hadn’t even heard of. This helped my writing stand out. As a result, my writing started blowing up. Within a few years, I went from zero to tens of millions of readers in top publications like Forbes, Fortune, TIME, and Harvard Business Review—something I couldn’t have even imagined before.

At a deeper level, applying the Outlier Algorithm facilitated a deeper transformation within me. In many ways, learning rare & valuable skills is following the Hero’s Journey—the most common archetypal myth that has existed across all human societies throughout time.

This essence of the journey is:

Individuals stepping away from the tried of true path of their culture.

Going into the depths of the unknown to reinvent themselves.

And then bringing that learning back to their culture so it can evolve.

We follow the same journey each time we learn a rare and valuable skill. When we choose to not follow the consensus, we begin a loop of the Hero’s Journey. We go from the known into the unknown. When we finally find something more valuable than the consensus and share it, we end one loop and set the stage for a new loop. Looking at the Outlier Algorithm this way helped me feel less alone and crazy. It made me feel part of a lineage. And it gave more meaning to sharing what I know with others.

Finally, with the Outlier Algorithm, I could now decode the quirks of many top investors and entrepreneurs.

I could now understand why Ray Dalio was going back into ancient history for new insights on today’s markets: History repeats itself. But sometimes it takes decades or even centuries to repeat itself. So people shouldn’t just use their own life experience to draw big conclusions. By going back further in history, Dalio found a more accurate way to predict the future that others overlook.

It explains why the #1 question that Peter Thiel asks new recruits and collaborators is:

What do you believe is true that no one else agrees with you on?

It’s a quick filter to know if someone is a consensus thinker or a contrarian thinker. If they can’t even think of one contrarian idea, they’re likely not a good fit.

It also explains why Elon Musk values engineering and design so highly and spends 80% of his time there rather than on “typical” CEO duties:

It’s valuable. When he and his team design products, they judge quality based on how closely it matches their platonic ideal of what they’re designing rather than how closely it mimics competitors. In other words, they use a higher standard for value.

It’s rare. He doesn’t follow the typical dogma of what business is. He redefines it. None of the other CEOs of car companies are designers and engineers. And most of them spend their days on business-related activities.

Bottom line…