The One Trait That Elon Musk, Ben Franklin, And Marie Curie Have In Common

Author’s Note: This article was written over 60 hours with love and care using the blockbuster mental model.

Jack of all trades. Master of none.

The warning against being a generalist has persisted for hundreds of years in dozens of languages.

“Equipped with knives all over, yet none is sharp,” warned people in China. In Estonia, it went, “Nine trades, the tenth one—hunger.”

Yet, many of the most impactful individuals—both contemporary and historical—have been generalists: Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, Arianna Huffington, Ben Franklin, Leonardo Da Vinci, and Marie Curie.

Are these legends just genius anomalies? Or are they models that we can all learn from?

My research over the past year shows that the latter is true. There is a surprisingly strong link between diversity of relationships/knowledge (being a generalist) and career success.

Many people fail to become successful generalists because schools and society tend to encourage focus on single expertise. As a result, few ever develop the necessary skillset.

The good news is that with practice and some of the tools in this article, anyone can become a successful generalist.

The Fundamental Challenge Of Being A Generalist

Meeting new people outside of our current circles and learning outside of our expertise is hard to justify.

For example, if you’re a marketing executive, it’s much easier to justify reading the latest marketing book than it is to read a classic book on evolutionary biology. Yet, reading that biology book might give you a completely novel idea that no one else in your field has.

In confronting this challenge, we must embrace the paradox of the usefulness of useless knowledge as poignantly shared by the expert on educational practices, Abraham Flexner:

..throughout the whole history of science most of the really great discoveries which had ultimately proved to be beneficial to mankind had been made by men and women who were driven not by the desire to be useful but merely the desire to satisfy their curiosity.

Here are six concrete strategies from some of the world’s top generalists (who also happen to be millionaire and billionaire entrepreneurs) to help you efficiently and systematically explore new areas…

#1: Go Straight To The Data So You Can Form An Independent Opinion

Ray Dalio is the founder of the largest hedge fund in the world, Bridgewater Associates, which has $169+ billion under management. His approach is based on a set of fundamental principles, which he explains in a 117-page treatise, which I summarized.

Core to Dalio’s philosophy is becoming an independent thinker rather than focusing on what you are taught by others:

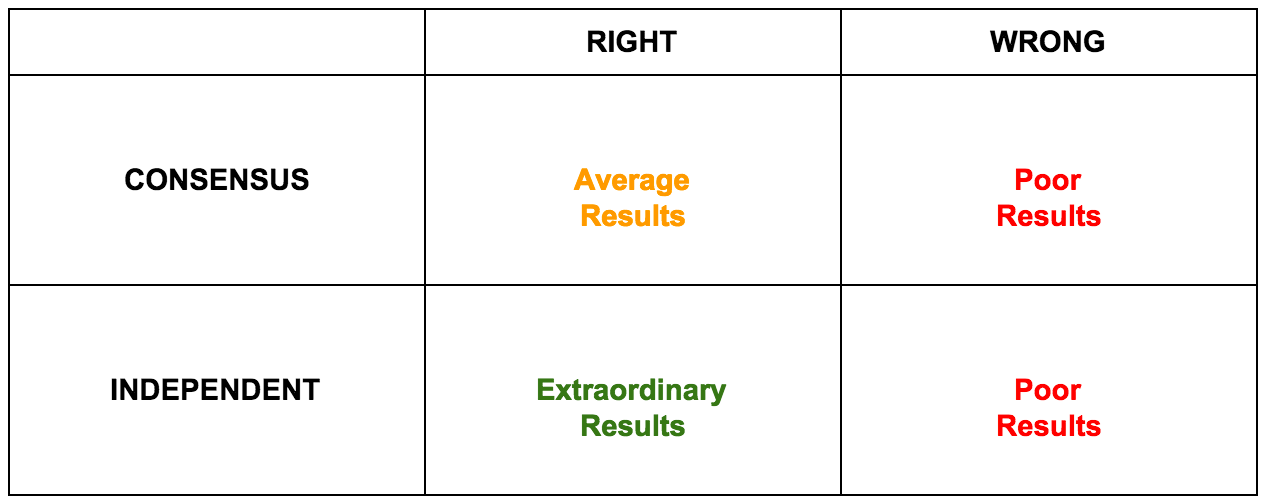

You have to be an independent thinker because you can’t make money agreeing with the consensus view, which is already embedded in the price. Yet whenever you’re betting against the consensus there’s a significant probability you’re going to be wrong, so you have to be humble.

In other words, according to Dalio, the key to being a successful investor is finding when the consensus is wrong and having an independent opinion that is right.

The same principle holds true in other fields such as venture capital. Famous technology investor, Peter Thiel, selects the founders he backs in part by asking them what they strongly believe that no one else does.

According to Dalio, the first step to becoming an independent thinker is to understand reality deeply. In order to do this early in his career, he ordered all the annual reports of Fortune 500 companies, then worked his way through the most interesting ones and formed opinions.

Warren Buffett took a similar approach. According to the book, Outsiders, he has kept up a habit of reading 3 annual reports a day for his entire career. When asked how to get smarter, Buffett once held up stacks of paper and said, “Read 500 pages like this every day. That’s how knowledge builds up, like compound interest.”

#2: Learn The Big Ideas In The Big Disciplines

Charlie Munger’s success as one of the world’s top investors and Warren Buffett’s longtime business partner did not come from having a laser-like focus on investment theory. Rather, he studied widely and deeply in many fields, including microeconomics, psychology, law, mathematics, biology, and engineering, and applied insights from these fields to investing.

Munger’s rules and quotes are excerpted from various talks that he’s given, which are featured in his book, Poor Charlie’s Almanack.

Rule #1: Learn Multiple Mental Models

The first rule is that you’ve got to have multiple models — because if you just have one or two that you’re using, the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your models.

It’s like the old saying, ‘To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.’ But that’s a perfectly disastrous way to think and a perfectly disastrous way to operate in the world.

Rule #2: Learn Multiple Models From Multiple Disciplines

…and the models have to come from multiple disciplines — because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department.

Rule #3: Focus On Big Ideas From The Big Disciplines

You may say, ‘My God, this [learning so many mental models] is already getting way too tough.’ But, fortunately, it isn’t that tough — because 80 or 90 important models will carry about 90% of the freight in making you a worldly-wise person. And, of those, only a mere handful really carry very heavy freight.

#3: Spend Less Time Trying To Be Original And More Time Reading Widely

Charlie Munger famously stated, “In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time — none.” Emerson Spartz, 28, embodies this ideal.

He dropped out of school at 12, taught himself to speed read, and created his own wide-ranging curriculum. Spartz has now read thousands of books, for a while even averaging a book per day.

Spartz’s broad reading brought him to the conclusion that “There are no original ideas. There are just people who aren’t widely read enough to realize their ideas aren’t original.”

Over time, Spartz developed theories on how to make sites go viral. He successfully tested those theories on Facebook Pages; many of which acquired millions of fans. He then progressed to testing his theories with media properties. Today, his company, Spartz Media, is a network of sites (like Dose.com and OMG Facts) with 45+ million visitors per month.

Spartz’s company uses a research and repurpose strategy. A proprietary algorithm finds trending articles with certain qualities and repurposes them for the site’s unique audience.

“In my experience,” Spartz says, “it is much faster and less risky to read more widely and repurpose what is already working, or has worked somewhere else, than to attempt to come up with an idea that you think is original but actually isn’t.”