The Threat To Knowledge Workers Is Not AI Or Automation. It’s Their Horrifying Lack Of Productivity

Author’s Note: This article is part of a series on productivity that was researched and written over hundreds of hours (yeah, I know, I’m fun at parties) using the blockbuster philosophy. Below are the three other articles in the series:

We’re In A Productivity Crisis, According To 52 Years Of Data. Things Could Get Really Bad.

The Brutal Truth About Life-Changing Opportunities We Overlook Every Day

Now back to your regularly scheduled programming…

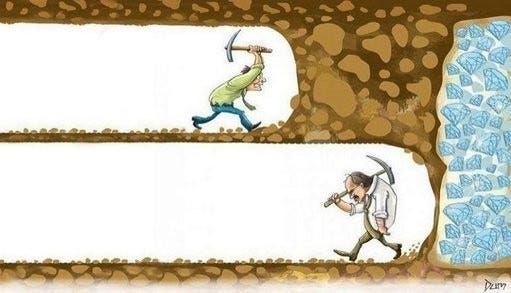

As I dive deeper into the history of productivity, the more I see how we are unproductive at being productive. As a result, the GIF below feels more like a brutal truth than a humorous joke.

Most of us probably think we’re the person confidently demonstrating how to use the wheelbarrow.

I hate to break it to you, but that’s not us.

We’re the other guy. We’re hustling. We’re using the latest gadget (ie, a wheelbarrow). We can’t fathom being much more productive — especially when we’re already working our butts off.

But…

Ultimately, there’s a major blindspot that sabotages us and stops us from properly using the metaphorical wheelbarrow. And, it’s not our fault. Until we see that blindspot, our potential is limited.

The Fundamental Productivity Blindspot Explains Why We Overlook So Many Life-Changing Improvement Opportunities Everyday

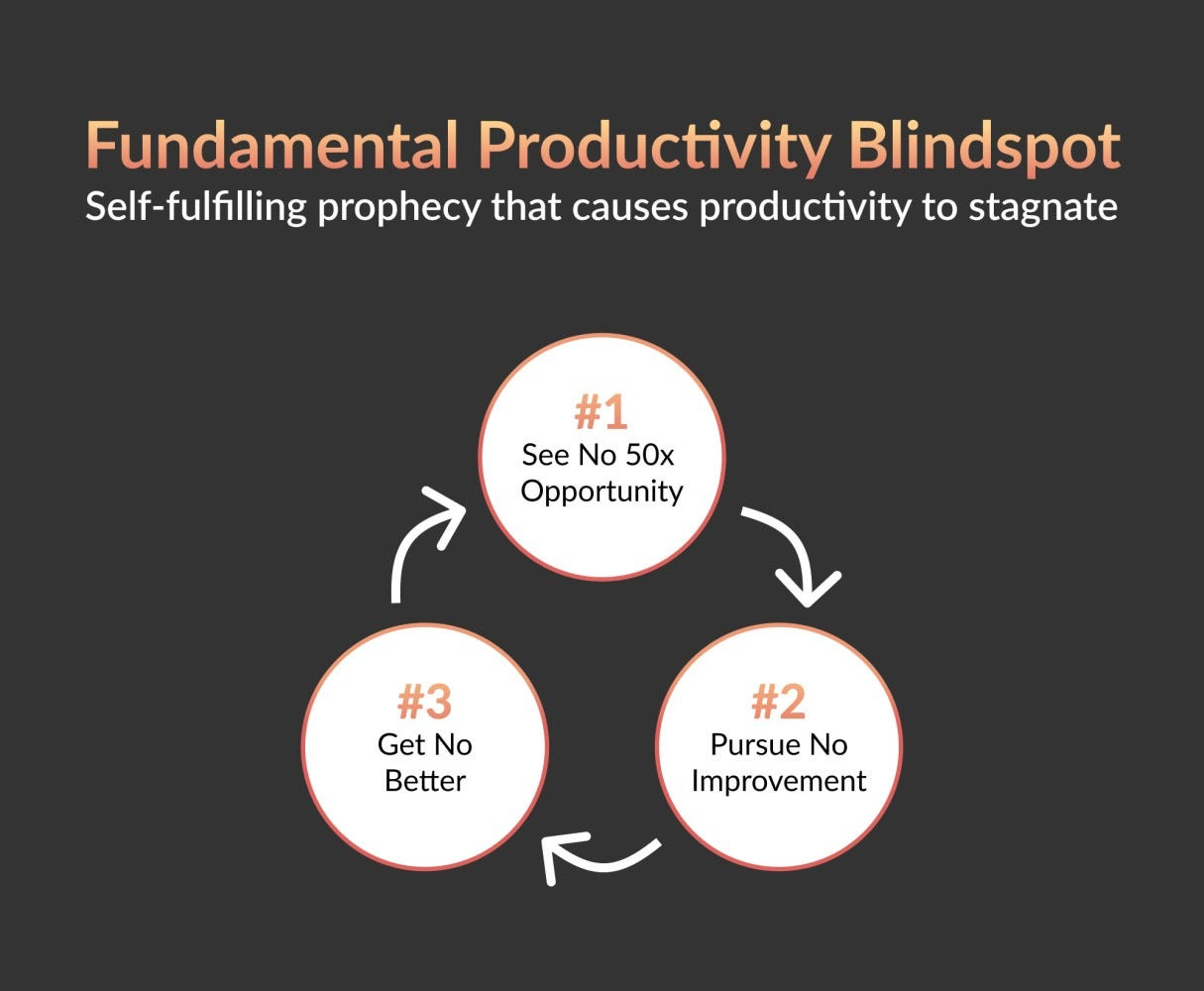

The Fundamental Productivity Blindspot is a vicious loop where:

We can’t see the immense opportunities for improvement right in front of us every day.

Therefore, we don’t devote much time to deliberate, continuous improvement.

As a result, we don’t improve, which reinforces our initial belief that there’s nothing to improve.

The visual below illustrates the loop…

As a result of the blindspot in contemporary work culture, we get hit by the following five symptoms…

We underestimate our potential to improve.

We overestimate how productive we are day-to-day.

We underestimate how unproductive we are day-to-day.

We underestimate the incredible power of continuous improvement because compounding is hard to understand.

We don’t understand what it means to be deliberate and systematic about improvement, so we settle.

It’s important to understand each symptom to fully grasp the magnitude of the Fundamental Productivity Blindspot…

Symptom 1. We drastically underestimate our potential to improve

In The Brutal Truth About Life-Changing Opportunities We Overlook Every Day, I share example after example of how, throughout history, we overlooked fundamental technologies sitting right in front of us for centuries. And one of the main reasons was that we simply could not see them. This phenomenon counters the conventional wisdom that as soon as some important innovation becomes feasible, somebody develops it.

Symptom 2. We drastically overestimate how productive we are day-to-day

On a day-to-day basis, there are many things that make us think we’re productive even when we’re not:

We cross off items on our to-do list.

We work hard.

We feel productive.

We compare our productivity to the norms rather than the potential.

As a result of these, we confuse busy work with productive work like the cartoon below:

Symptom 3. We drastically underestimate how unproductive we are

It’s easy for “waste” that destroys our productivity to remain hidden.

For example, according to research shared by Cal Newport in A World Without Email, the average knowledge worker is interrupted every 20 minutes by a notification.

And for each interruption, there is a cost:

It takes an estimated 10–15 minutes of recovery time to get back to where we were, if we ever do.

We make more mistakes.

We lose time for deep focus, which is already very rare.

Yet, these costs are often hidden because they’re short and spread throughout the day. As a result, we never see their cumulative cost illustrated by the infographic below:

Symptom 4. We underestimate the incredible power of continuous improvement because compounding is hard to understand

Understanding both the power of compound interest and the difficulty of getting it is the heart and soul of understanding a lot of things.

—Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s Long-Time Business Partner

The image below shows the power of small, hidden improvements in an even more tangible way…

On the surface, reading 25 pages a day might not sound like much. But, if we read just 25 pages of books per day, we can read 30–40 books in a year. That’s enough to develop real expertise in a new area every year. That’s enough to help you do your job better, get a raise, and change the overall trajectory of your life.

Symptom 5. We don’t really understand what it means to be deliberate about improvement, so we settle

Many people today proudly proclaim to be lifelong learners. They do so because they love learning and they try to improve whenever they can. They follow smart people on Twitter. They read their trade publication daily. They read a few books per year. And then pat themselves on the back.

However, as I’ve spent more time studying, practicing, and teaching learning how to learn along with the history of productivity improvement, it has become more and more clear that what people call lifelong learning is more aptly called hobby learning (and sometimes even junk learning).

For example, I vividly remember experiencing this mismatch between being a hobbyist and a professional first-hand. Growing up, I played tennis competitively. In high school, I could beat almost everyone with my weak hand. In my state, I was one of the top players, which meant I won most of my matches. But, when I tried to play top nationally ranked opponents, I couldn’t even stay on the court. It was embarrassing. When I eventually got to see the intensity of how they practiced, I understood why. These players often practiced twice per day. They had one-on-one coaching daily. And, they had trainers keeping them fit and helping them avoid injuries. In addition, they exclusively practiced with players at or above their level, which is why I rarely even saw them.

The same phenomenon happens with learning. We overestimate our ability because we don’t know what the levels above us look like…

First, very few people consistently set aside significant time for learning. Even fewer set aside time for learning how to learn better.

Second, most people don’t have the core frameworks for improving productivity that have been proven over and over throughout history. More on these frameworks later.

Summary: The Fundamental Productivity Blindspot in contemporary work culture leads to the five symptoms below…

We underestimate our potential to improve.

We overestimate how productive we are day-to-day.

We underestimate how unproductive we are day-to-day.

We underestimate the incredible power of continuous improvement because compounding is hard to understand.

We don’t understand what it means to be deliberate and systematic about improvement, so we settle.

As a result of these, we get stuck in a self-fulling prophecy where:

We don’t see opportunities to improve that are right in front of us.

Therefore, we don’t invest enough time and rigor into improvement.

As a result, we don’t improve.

Implication: The Fundamental Productivity Blindspot has vicious consequences. And, it may be a significant cause of the silent productivity crisis we’ve been in over the last 52 years.

Fortunately, there’s good news… really good news.

Because the bar is so low, I now believe that the average knowledge worker can become 50x more productive over the course of their lifetime if they are deliberate about setting aside time for improvement and improving how they improve.

The reason I believe that 50x is possible now is because I’ve spent hundreds of hours studying the incredible 50x increase in productivity over the 20th century, whose causes many seem to have forgotten. Here’s the history lesson you didn’t know you needed…

History Already Taught Us How To 50x Our Productivity

The most important, and indeed the truly unique, contribution of management in the 20th century was the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the manual worker in manufacturing.

—Peter Drucker, father of academic discipline of management

Crazy, right?

I remember how floored I was when I first read the quote above. A 50x increase in productivity of the average person felt like a typo. So, I had to learn more…

First, I did a deep dive to understand why productivity boomed between 1870–1970. I thought I’d quickly find out the reason and then write an article on it. About 100 hours later, I published In 1911, a genius revealed a forgotten science of how to be 50x more productive without working more hours. Then, 100 hours turned into hundreds and one article turned into a series.

Throughout the process, I gained a deeper understanding of why the productivity of the average manual worker skyrocketed by 50x. And the ultimate conclusion I came to is perfectly summarized by Peter Drucker:

In the decade after Frederick Winslow Taylor first looked at work and studied it, the productivity of the manual worker began its unprecedented rise… On this achievement rest all of the economic and social gains of the 20th century.

—Peter Drucker

To summarize Taylor’s system for improving productivity, he:

Broke down each step of the production process into one-minute tasks.

Studied how these tasks were being done at a granular level (time and movement tracking).

Systematically experimented to find the one best way to do those tasks..

Standardized the one best way across all workers.

I created the following cheat sheet to give a deep overview (full explanation here):

While this 50x productivity framework sounds basic, it’s deceptively powerful. It’s built on three timeless ideas that have increased productivity for eons — specialization, continuous improvement through experimentation, and standardization:

Timeless Productivity Principle 1: Specialization

Rather than having one person do 30 different tasks throughout the day. Have them focus on one and do it over and over. This simple insight is so powerful because it means that workers:

Need less training

Are more focused because of less task switching

Get more done

Have fewer errors

Improve faster

Because of specialization on the assembly line, complicated craft skills that took years of apprenticeship to learn were replaced by unskilled workers who could learn how to do their one-minute task in a few hours and then get in 500+ reps of practice per day.

To consider the specialization’s scale of impact, consider the first page of economist Adam Smith’s magnum opus, The Wealth Of Nations. At a pin factory, just 10 employees are able to produce an astounding 48,000 pins per day as a result of a division of labor, in which each person specializes in part of the process. Smith estimated that if each of these 10 workers did every step of the process themselves, they’d collectively create just 200 pins per day. In other words, specialization boosted their productivity 240x.

Interestingly, the top investor in history, Warren Buffett, also considers specialization (circle of competence in his words) as one of his central mental models for making better investing decisions. He only makes investments in a very small set of companies where he has a comparative advantage in understanding the company’s value. And while we may not be investing billions of dollars like Buffett, we are constantly making decisions about where to invest our time and money.

Bottom line: While many knowledge workers consider themselves specialists, by the standards of the world’s most productive manufacturers, they are hardcore generalists.