The Brutal Truth About Life-Changing Opportunities We Overlook Every Day

Author’s Note: This article is part of a series on productivity that was researched and written over hundreds of hours (yeah, I know, I’m fun at parties) using the blockbuster philosophy. Below are the three other articles in the series:

We’re In A Productivity Crisis, According To 52 Years Of Data. Things Could Get Really Bad.

The Threat To Knowledge Workers Is Not AI Or Automation. It’s Their Horrifying Lack Of Productivity

Now back to your regularly scheduled programming…

It took a single chance event for one of history’s most profound shifts to happen.

Working from home was possible in the early 2000s.

It could’ve changed everything starting 20 years ago.

Yet, it wasn’t until a worldwide pandemic forced people to work from home that companies around the world actually made the shift en masse.

How could this happen?

Why wouldn’t we capitalize on such a monumental opportunity as soon as it became possible?

This one example, when fully understood, challenges our most fundamental understanding of how productivity and science progress.

To understand the significance of what I’m saying, we must first understand that…

Work From Home Is One Of The Most Important Innovations Of This Millennium

When historians look back on the 21st century, working from home will be one of the big events just like working from factories was in the 19th century.

Teachers will tell their students about how working from home fundamentally changed how companies recruit globally, work asynchronously in different time zones, structure their organization chart, communicate and build their culture, and locate/design their offices.

Then, they’ll share how this domino led to the fall of even bigger dominoes. They’ll talk about how work from home:

Empowered everybody in the world with talent and the Internet

Changed how employees balance home and work

Changed the structure/location of tech centers

Changed where people live between cities, states, and countries thus changing balance of power in politics

Reduced the power of government, because people could more easily relocate if they didn’t like the direction a region was moving

In retrospect, the change will seem obvious.

Yet a few things disturb me…

If there wasn’t a pandemic, it might have taken a few more decades for the shift to happen.

Even the smartest innovators and venture capitalists (like famous investor Marc Andreessen—more on him later) underestimated its potential/feasibility.

Even more concerning, there had been surprisingly little experimentation with remote work prior to the pandemic.

The shift of hundreds of millions of people who spent their whole life working in an office or being educated at a school was surprisingly seamless. In other words, the #1 challenge stopping the shift wasn’t the feasibility or difficulty.

What happened here?

Conventional wisdom says that if an innovation is feasible and valuable, it will be immediately implemented.

The shift to working from home shows that conventional wisdom is flawed. Simple, big innovations to science and work regularly sit on the shelves for decades and even centuries. Case in point…

Suitcase Wheels Weren’t Invented Until The 1980s

History is replete with feasible, world-changing scientific insights, productivity improvements, or technological breakthroughs stalling for centuries:

Gunpowder: “The Chinese invented gunpowder but used it only for fireworks,” according to researcher David Nye, author of America’s Assembly Line.

Wheel: “The Aztecs invented the wheel but used it only on children’s toys,” according to David Nye.

Steam Engine: “The ancient Greeks invented a small steam engine but thought it a mere curiosity,” according to David Nye. Furthermore, “More than fifty years elapsed between Newcomen’s original design, which was good for pumping water out of mines but not much else, and Watt’s key improvement of the separate condenser, which opened the path to a bigger range of applications and, more importantly, to further development,” according to an independent researcher, Jason Crawford.

Concrete: “The Romans invented poured concrete, but the process was forgotten and was reinvented centuries later,” according to David Nye.

Electricity: “The ability of amber to collect static electricity was known to the ancient Greeks. More than 2,000 years later, in the 1600s, William Gilbert discovered and documented that other materials can do this as well. Then, again, nothing happened for decades. This pattern was seen even in the 1700s and 1800s, when science had gained a lot more momentum. For instance, the battery was invented in 1799, and an electric arc light powered by it was demonstrated in 1809. But there were no more discoveries in the physics of electromagnetism for twenty years, and electricity didn’t become industrially significant until the very late 1800s,” according to Jason Crawford.

Penicillin: “Penicillin was discovered in 1928 by Alexander Fleming, but was ignored for over a decade because it was deemed too difficult to produce in sufficient quantity and purity even for further testing, let alone industrial production. It wasn’t picked up again until Howard Florey’s laboratory started investigating it in the early 1940s (and even then progress was slow because they were vastly underfunded, which seems shocking in retrospect),” according to Jason Crawford.

Scurvy Cure: A regimen of lime juice as a preventative and cure for scurvy was demonstrated in 1747 (through an early, crude, controlled experiment), but not adopted as policy by the British navy for more than 40 years.

Gunpowder. The wheel. Concrete. Electricity. The steam engine. These are some of the most fundamental technologies we take for granted today. But, knowing what I know now, I feel lucky. Many of these could’ve taken centuries longer.

Researcher Anton Howes gives more context to the situation in his paper, The Spread of Improvement: Why Innovation Accelerated in Britain 1547–1851:

Take John Kay’s flying shuttle, which is today famous for improving the efficiency of weaving cotton. What makes the invention so extraordinary is that it could easily have been developed centuries prior. Bennet Woodcroft, a nineteenth century compiler of patent records, expressed his astonishment that the use of shuttles on a horizontal loom had been “performed for upwards of five thousand years, by millions of skilled workmen, without any improvement being made to expedite the operation, until the year 1733”. And all Kay had added was some wood and some string — it was an improvement that required no new materials, nor any advanced scientific knowledge…

Rather than asking why the flying shuttle was invented in 1733, we should ask why it was not invented centuries earlier: one of the most revolutionary innovations of the Industrial Revolution was a minor adjustment to an ancient industry, applied to an ancient technology, using ancient materials, and applying no new scientific knowledge.

Later, Howes points out another key invention that could’ve been invented hundreds of years earlier—the wheel:

Chinese innovators had developed multi-spindle spinning wheels and treadle looms as early as the eleventh century. By 1690 they had even contrived a “proto Bessemer converter”, which would not be developed in Britain until the 1850s. The seed drill of 1701… was another remarkably simple improvement to an ancient industry: agriculture. It, too, had been anticipated in China before the third century; and it was even used in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC. The technology did not appear in Europe, let alone in Britain, until the sixteenth century. Of course, many of the innovations of the Industrial Revolution did require prior scientific or technological advances. But the above examples demonstrate that innovation could fail to occur even when all of the incentives were in place.

Finally, in In 1911, a genius revealed a forgotten science of how to be 50x more productive without working more hours, I share how inventions are not alone. Simple productivity improvements like the professions of bricklaying, assembly, and shoveling had stalled productivity for thousands of years even though there were easy ways to improve them:

When reading about the drastic improvements in shoveling, bricklaying, and assembly, my mind was boggled. I didn’t understand how fields that had been around for thousands of years could be improved so easily and drastically — not by complex theories but by a simple process anyone could replicate.

Summarizing the phenomenon of innovation stagnation, researcher David Nye, author of America’s Assembly Line, says:

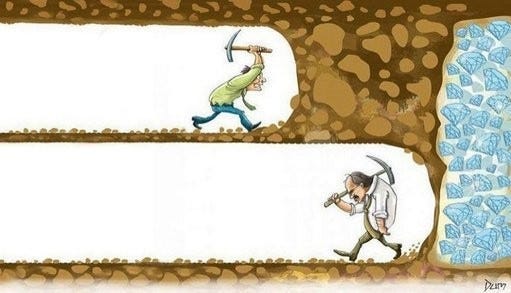

Innovation on a particular device may cease for decades or even centuries before someone reconceptualizes its design or its use.

A society may create a variety of separate objects without ever combining them to make something that, when finally invented, seems obvious in retrospect.

Elon Musk adds additional context with the following quote from a TED interview:

People are mistaken when they think that technology just automatically improves. It does not automatically improve. It only improves if a lot of people work very hard to make it better, and actually it will, I think, by itself degrade, actually. You look at great civilizations like Ancient Egypt, and they were able to make the pyramids, and they forgot how to do that. And then the Romans, they built these incredible aqueducts. They forgot how to do it.

—Elon Musk

To summarize…

These examples and quotes show how world-changing ideas can hide in plain sight for decades, centuries, or even millennia. The creation or adoption of improvements is not guaranteed or steady.

Even the people who are most well-positioned to see the potential of an improvement have trouble seeing its potential. Millions of people can practice a skill every day and still miss simple innovations that seem obvious in retrospect. Another case in point is self-made billionaire Marc Andreessen, the co-founder of Netscape (the first modern internet browser) who is also one of the world’s most prominent venture capitalists…

The Marc Andreessen Blindspot

In an enlightening 2015 interview on the Tim Ferriss Show, Matt Mullenweg, creator of WordPress and founder of Automattic (a distributed company with hundreds of people working across the world at the time), describes pitching Andreessen for funding:

When we first pitched him, the whole meeting was about how distributed companies were a terrible idea. And he was like: well what do you know that every other tech company that’s been big in history doesn’t? The Facebooks, the Googles, the Microsofts, the everything. And so why should you do something different?

Looking back on the meeting, Mullenweg says the meeting was instructive in retrospect, but at the time, he didn’t think so:

I thought it was the worst meeting of my entire career.

Mullenweg’s words stuck with me for years. I wondered:

How could one of the most innovative innovators (Marc Andreessen) miss one of the biggest shifts in how humans work in history?

After all, venture capitalists are paid to think from first principles (rather than what worked in the past) and make bold non-consensus bets.

But, what vexed me even more was the idea that if Marc Andreessen could miss remote work, what does that say for how society misses other important innovations? Andreessen was not alone after all. First, his criticisms of remote work were conventional wisdom. Second, it is common for inventive people to not see huge innovations right in front of them. For example…

Alfred Wallace never wrote up his theory of evolution because he felt that it was so obvious that it wasn’t worth writing up. Darwin beat him to the punch and very few people have even heard of Alfred Wallace.

In one interview, Mark Zuckerberg remembers driving into San Francisco in the early days of Facebook seeing billboards for huge tech companies, and thinking to himself that he might one day create a company that was that large. Little did he know that Facebook would be that company. Little did he know that he was already running that company.

In fact, this phenomenon is so common in Silicon Valley that there is a truism that huge technological breakthroughs seem like toys at first.

But, all credit to Andreessen. In 2021, he penned a blog post that was a 180-degree shift from his previous stance, even going so far as to say the following about remote work:

It is perhaps the most important thing that’s happened in my lifetime, a consequence of the internet that’s maybe even more important than the internet.

—Marc Andreessen

A year later, his venture capital firm reorganized to be a remote-first company.

I bring up this example not to show how very smart thinkers have gaps in their thinking or how venture capitalists inevitably miss investments in big winners. Rather, I think the Marc Andreessen Blindspot is instructive on a few levels:

Big innovations are not obvious. Just because a technology makes something possible that seems obvious in retrospect, it doesn’t mean it’s obvious in the moment. Even if the innovation is one of the biggest innovations and the people analyzing them are some of the world’s best innovators.

Andreessen was being logical. Almost all of the biggest tech companies in the world up to that point had been in-person and based in Silicon Valley. So locating their headquarters and efforts in Silicon Valley made a lot of sense. Furthermore, a tech startup has to beat incredible odds in order to succeed. Why invest in a startup that is making such a risky bet not related to its core product? Even if Andreessen believed that distributed work might be the main model in the future, betting the company that it would happen at that exact moment in history rather than decades in the future was not completely illogical.

In summary…

The Marc Andreessen Blindspot is the pattern that simple, life-changing opportunities for improving the world, our companies, and our lives can sit on the shelf in perpetuity. Their potential is invisible not only to the general populace but to the smartest, most inventive people in the world closest to them.

At a fundamental level, we should all care about the Marc Andreessen Blindspot because it means that there are huge opportunities for personal growth and productivity improvement sitting right in front of us that we have the ability to capitalize on, but we can’t see. It means the same for broader company, scientific, and societal opportunities.

The more I’ve wrestled with these implications of the Marc Andreessen Blindspot, the more I’ve come to believe we need a fundamentally new worldview for thinking about improvement. Below are the five pillars of that framework: